Automotive Art 33 – Trevis-Offenhauser

Racing cars that were exclusively on US racetracks are often almost completely unknown in Europe. However, that doesn’t make them uninteresting. Often the engineers on the other side of the Atlantic found interesting detail solutions and fine design for their oval race cars. This time, Bill Pack highlights a car that successfully competed in the Indianapolis 500 in 1961.

Welcome back to a new part of our monthly Automotive Art section with photographer and light artisan Bill Pack. He puts a special spotlight onto the design of classic and vintage cars and explains his interpretation of the styling ideas with some interesting pictures he took in his own style.

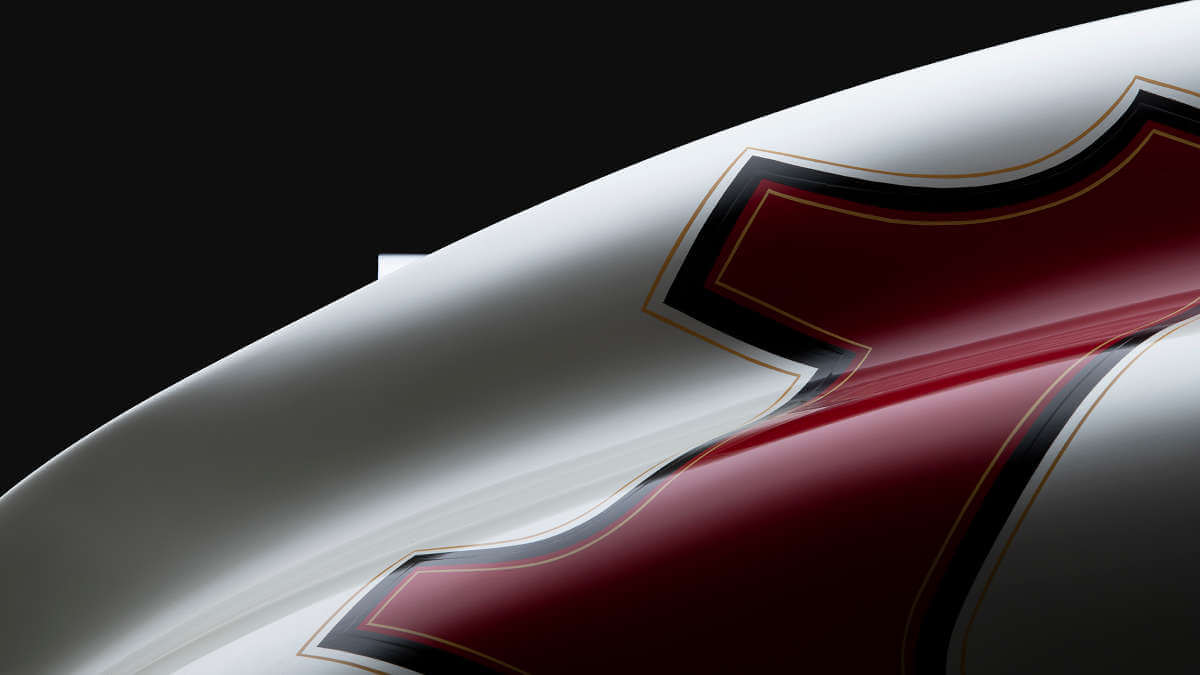

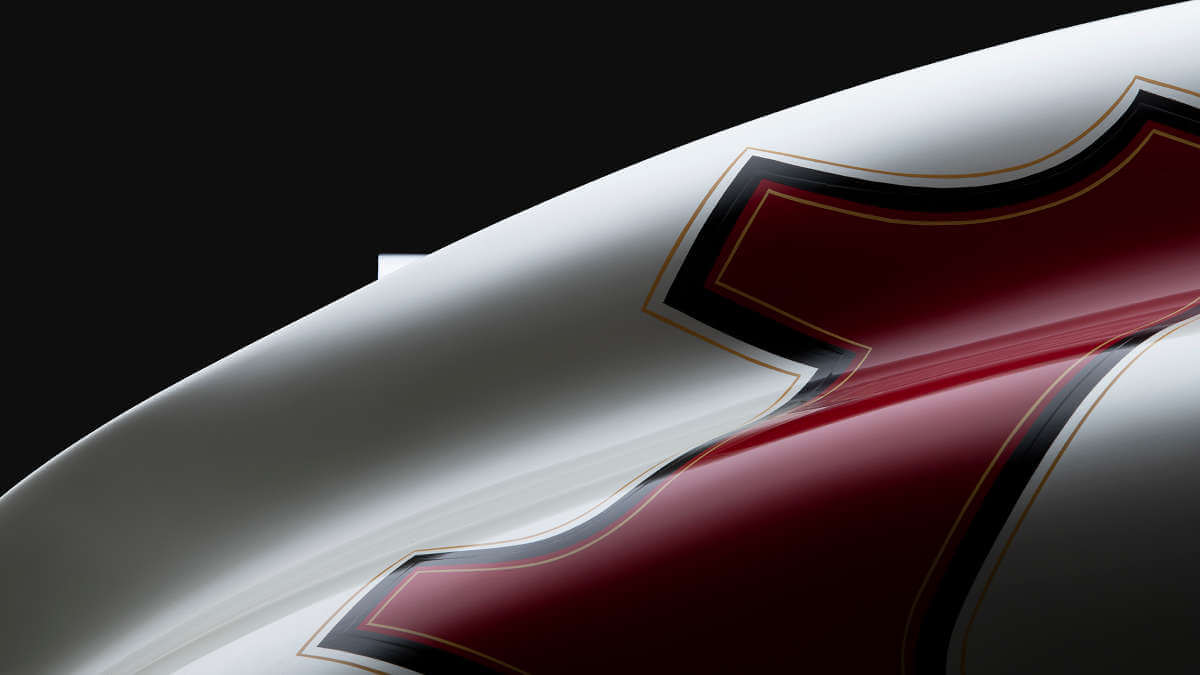

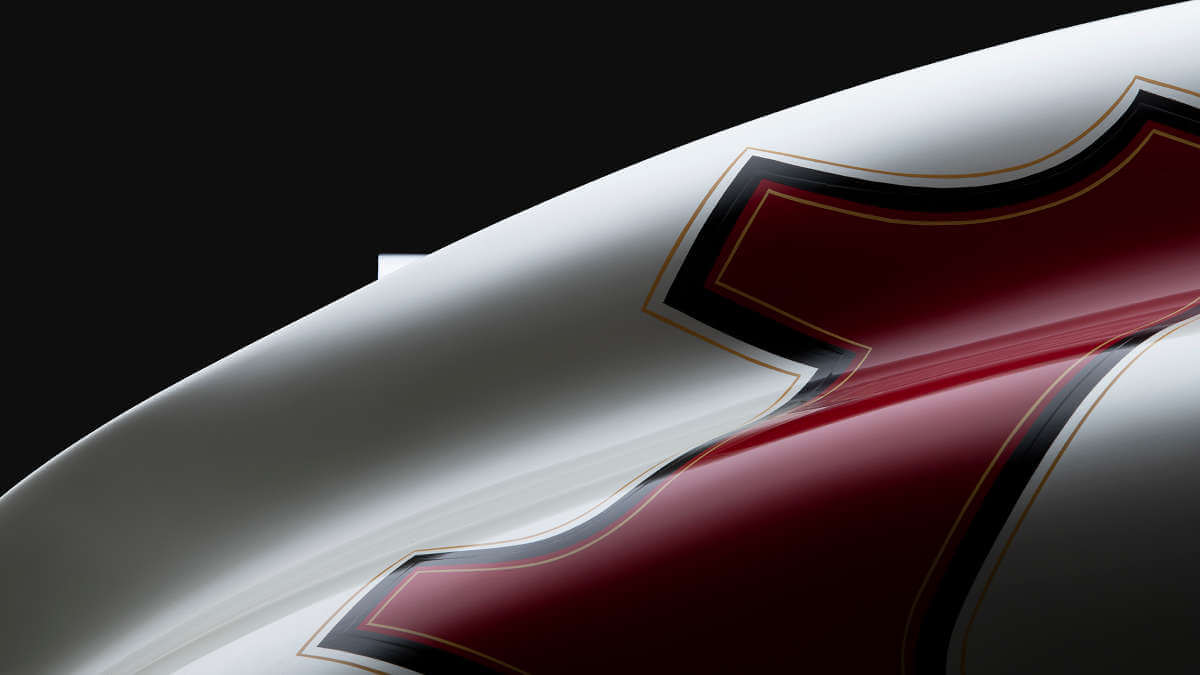

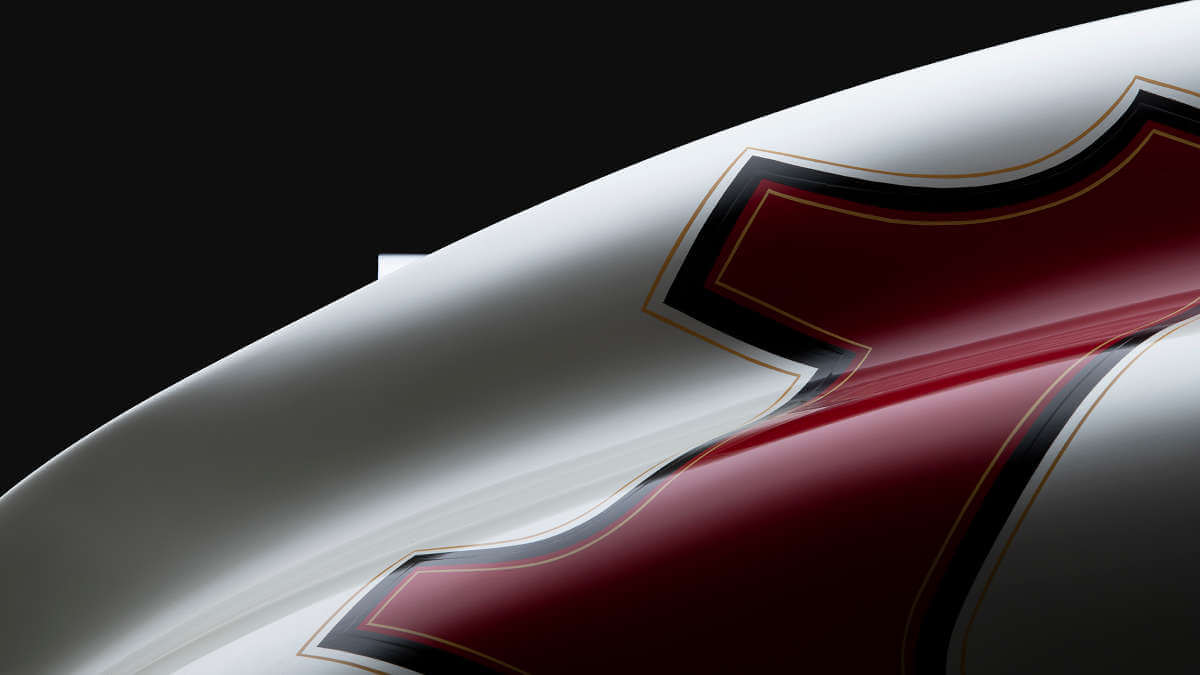

Into The Mind Of The Designer – by Bill Pack

It is easy to learn lots of facts and information about any automotive designer. We learn what great shops they worked for, what model of cars they designed and the innovations they have brought to the industry. We know about them, but we do not know them. With my imagery I attempted to get into the soul and spirit of the designer. By concentrating on specific parts of the car and using my lighting technique, I attempt to highlight the emotional lines of the designer.

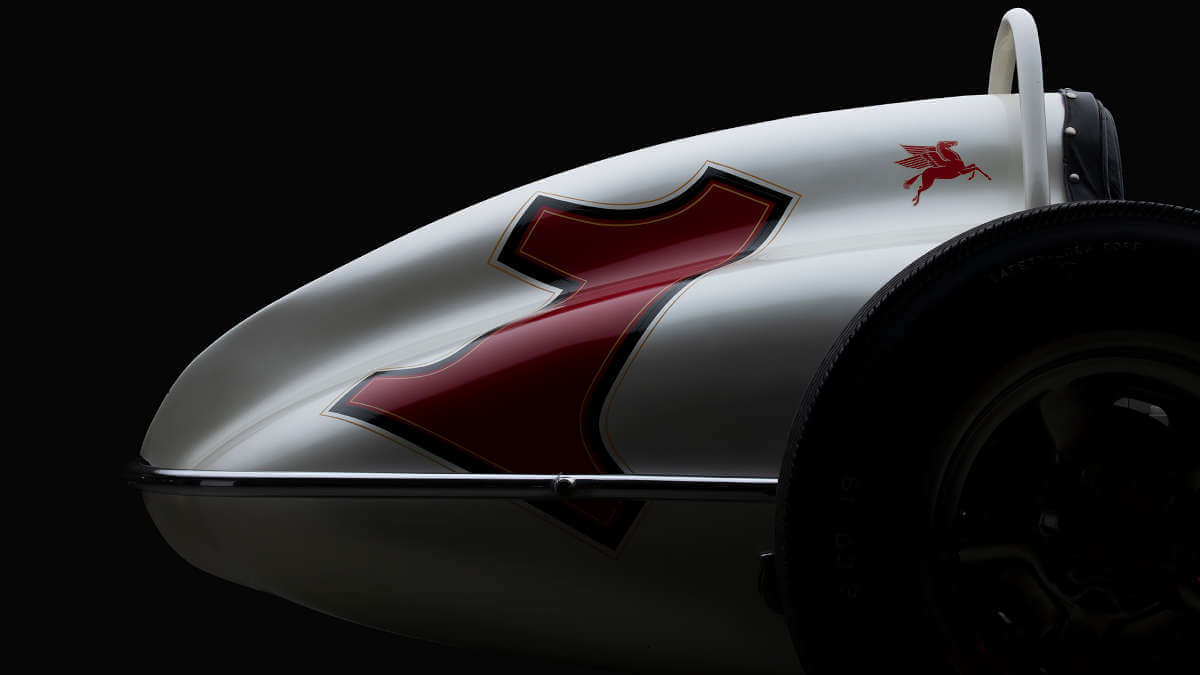

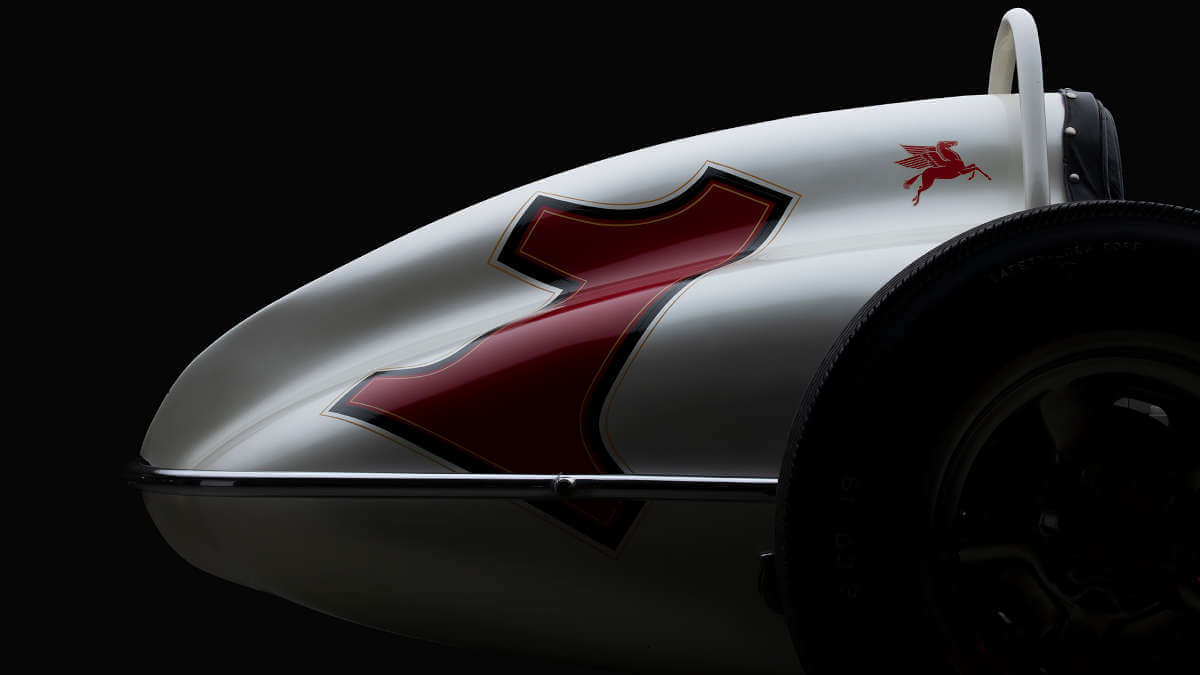

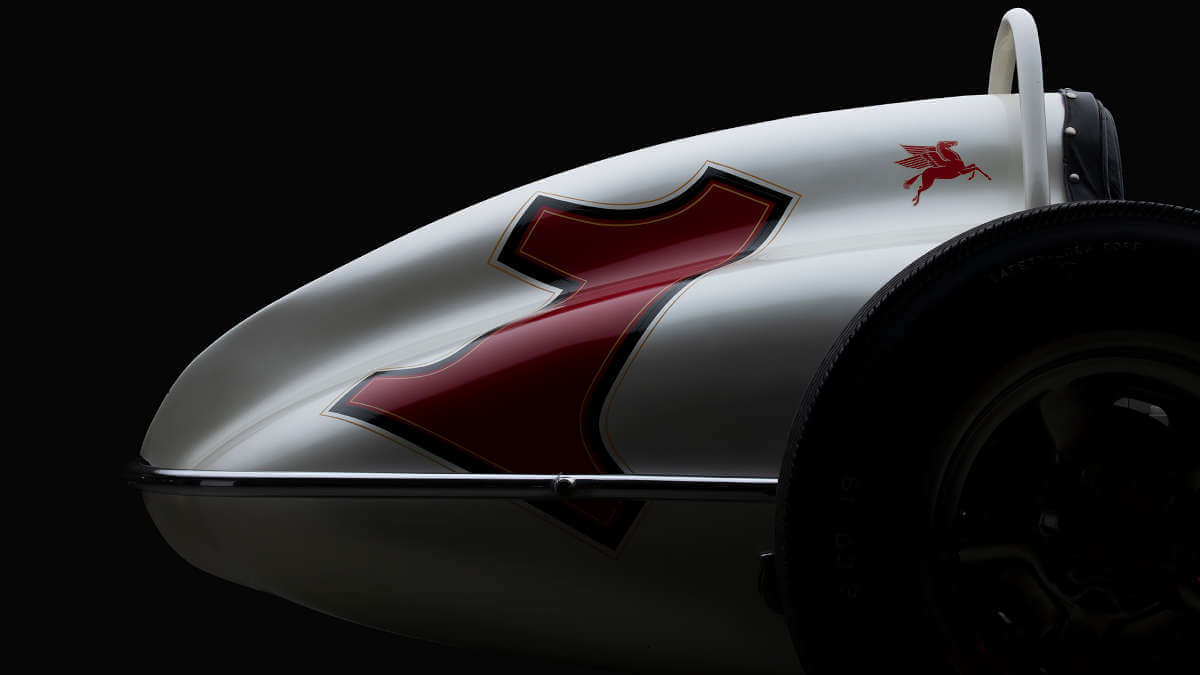

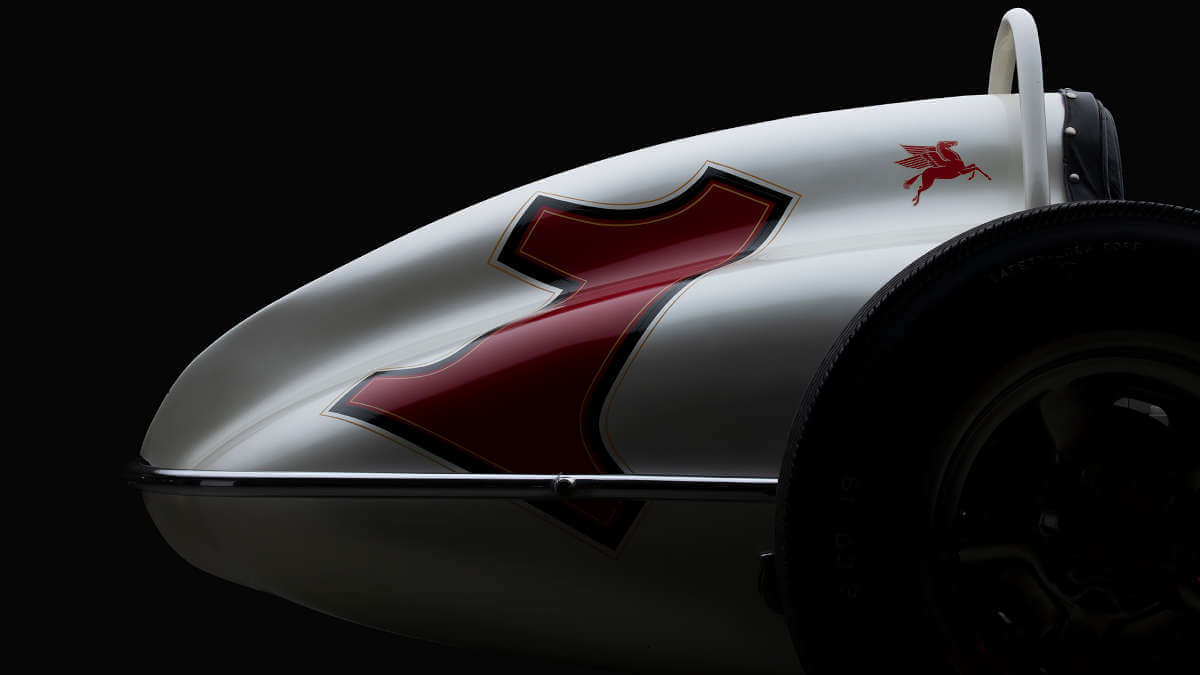

1961 Trevis-Offenhauser – Designed by A.J. Watson

The name on the car is Trevis-Offenhauser, but the DNA or origins of the car is all A.J. Watson.

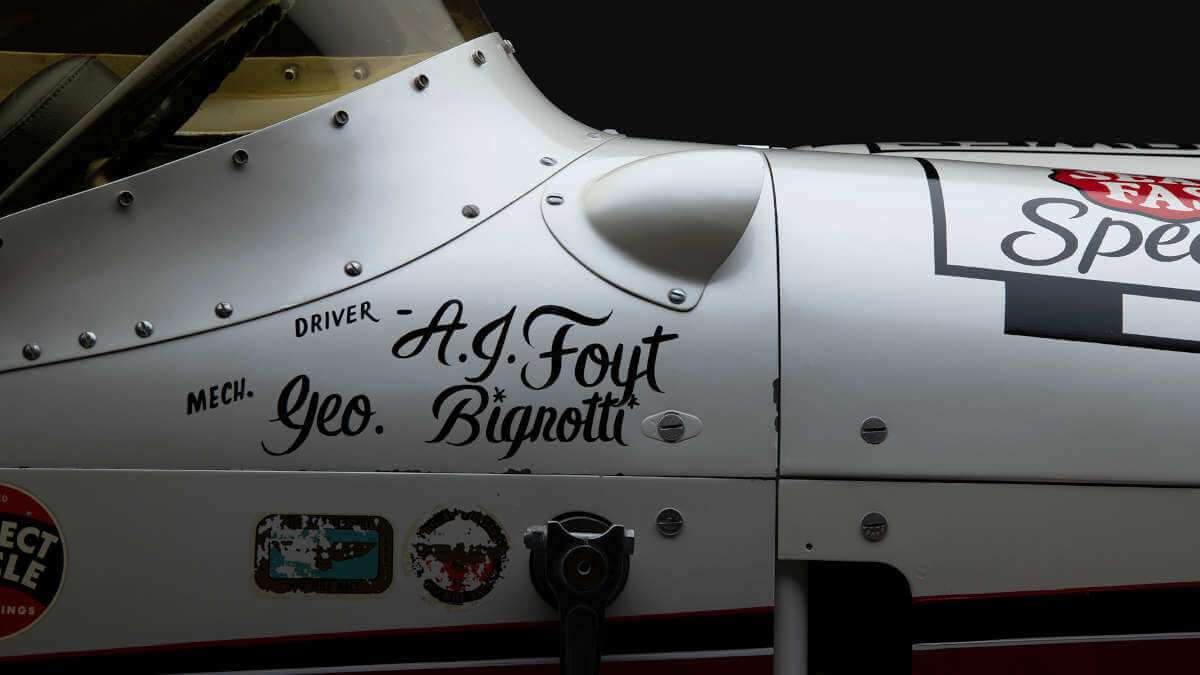

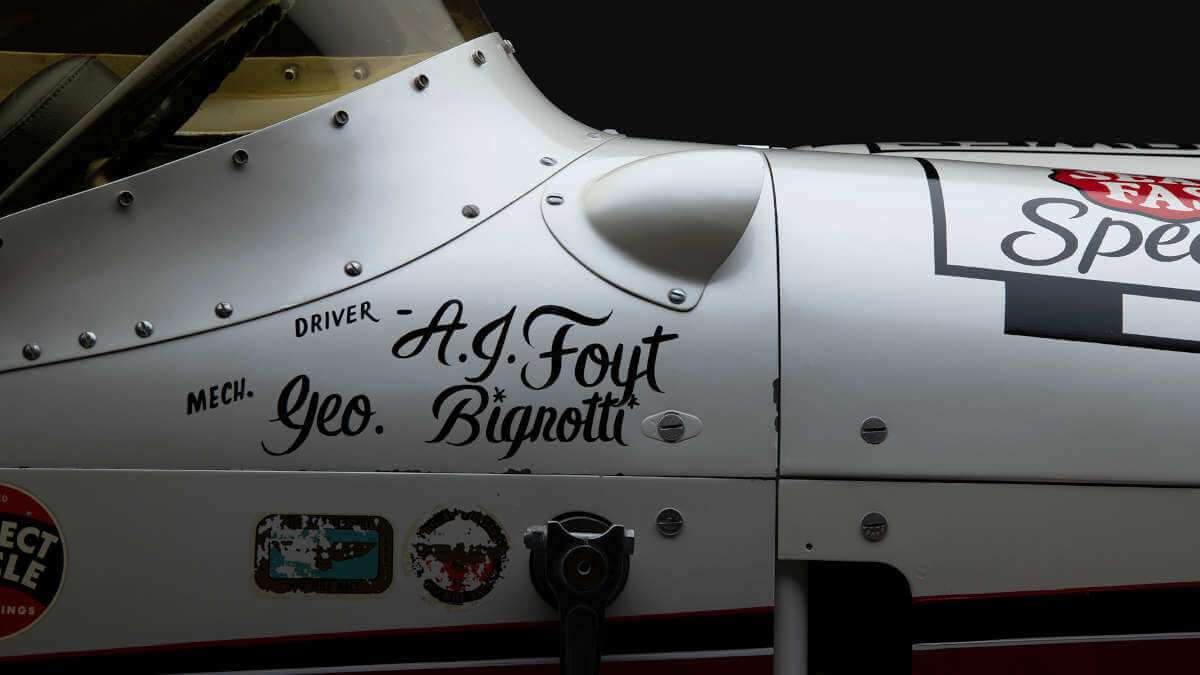

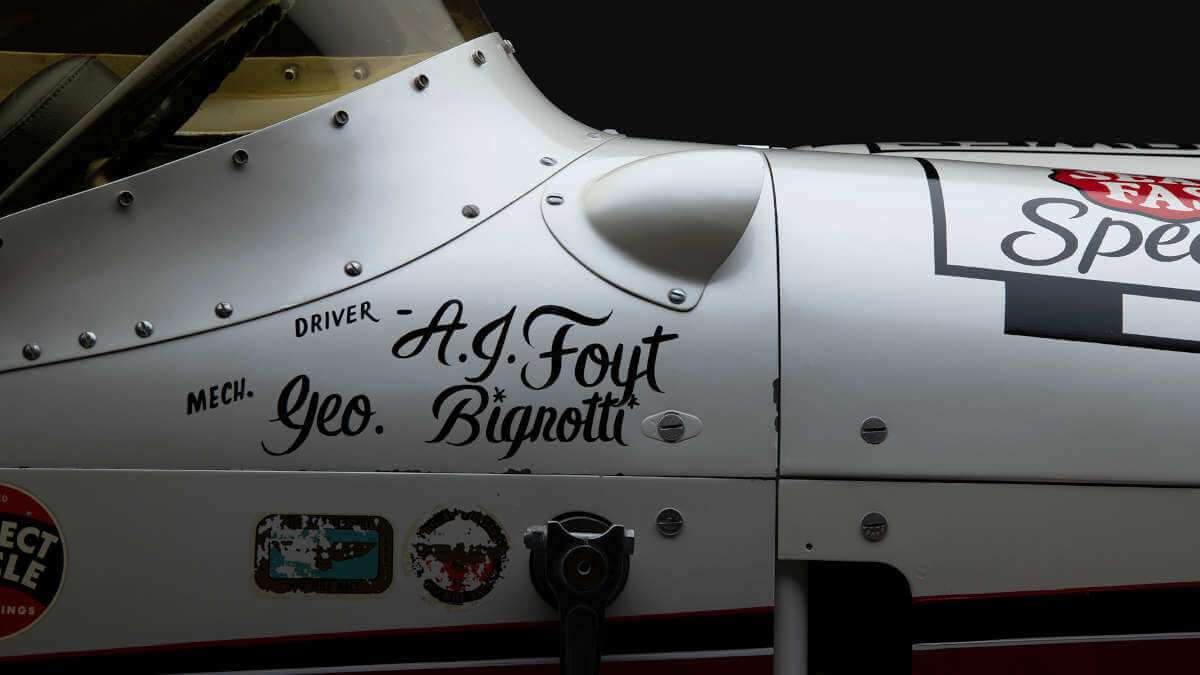

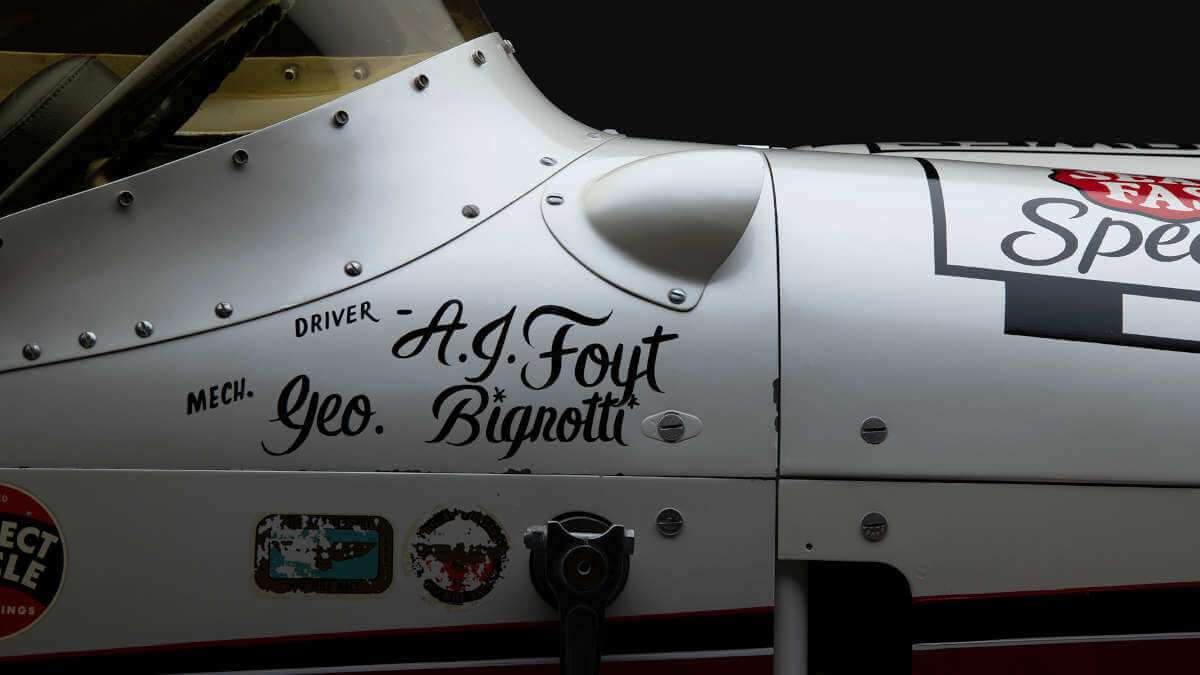

In the summer of 1960 famed driver A.J. Foyt’s car was sponsored by the Bowes Seal Fast Company and co-owned by Robert Bowes and crew chief George Bignotti. Bignotti wanted a new car to campaign for 1961. At the time builder A.J. Watson’s roadster was tried, proven and in such high demand that none were available. Bignotti figured out how to solve this dilemma. He hired Floyd Trevis, because of his success as a builder and for his friendship with Watson.

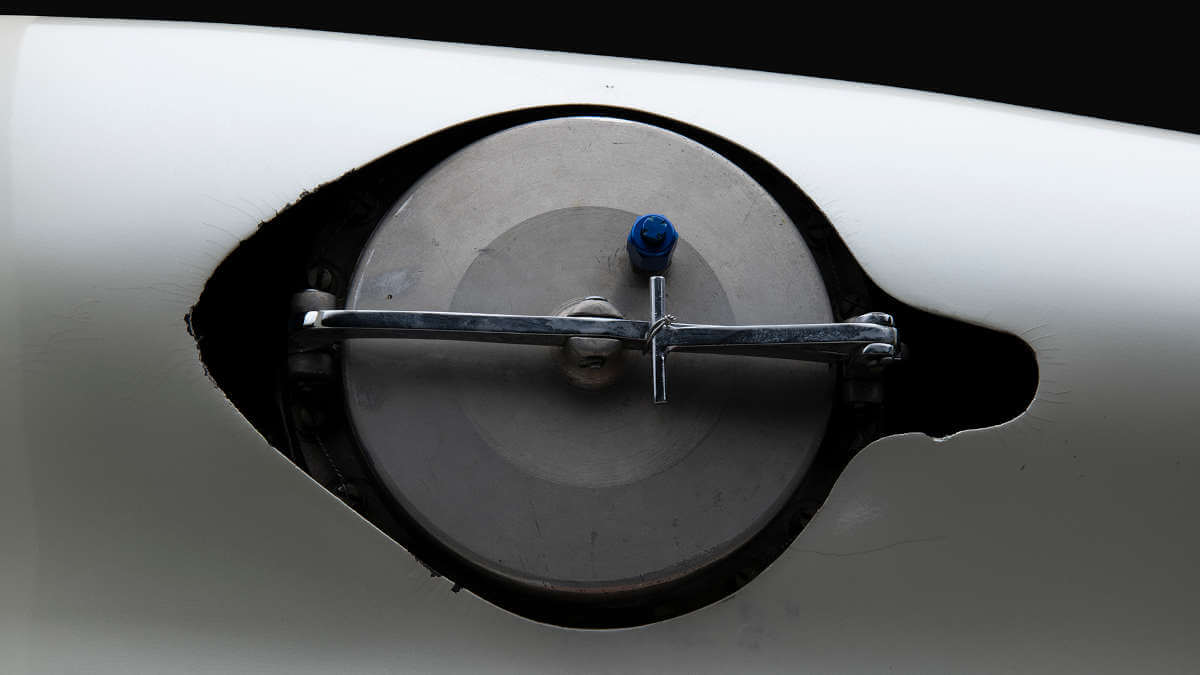

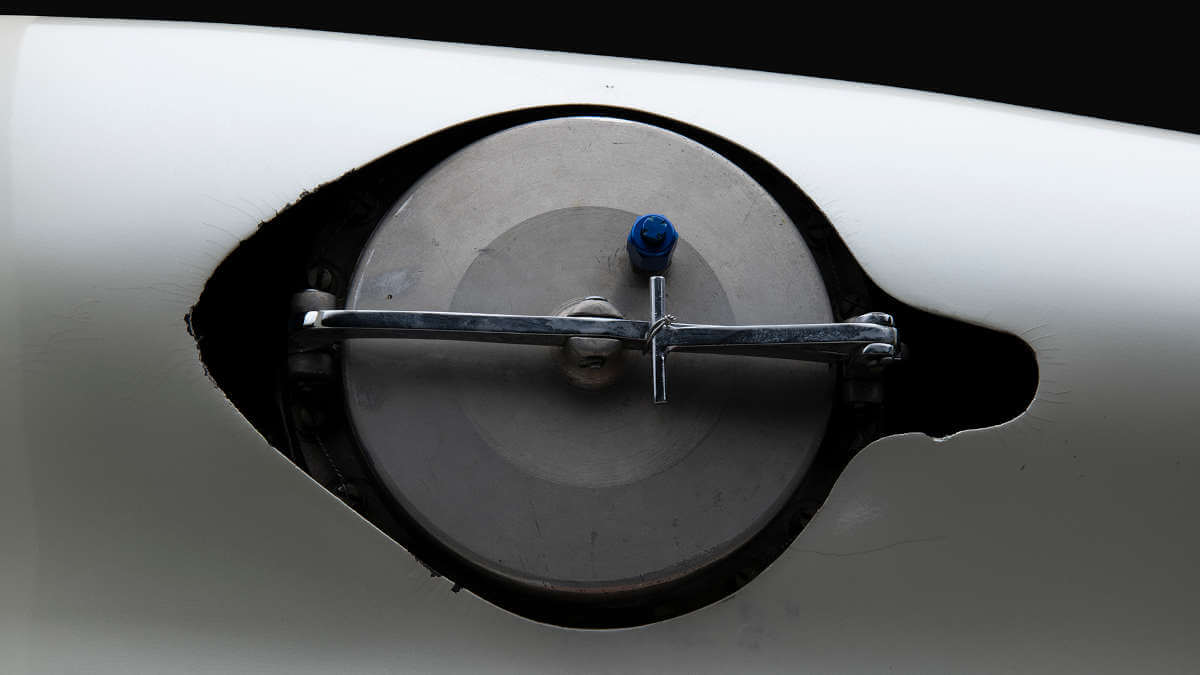

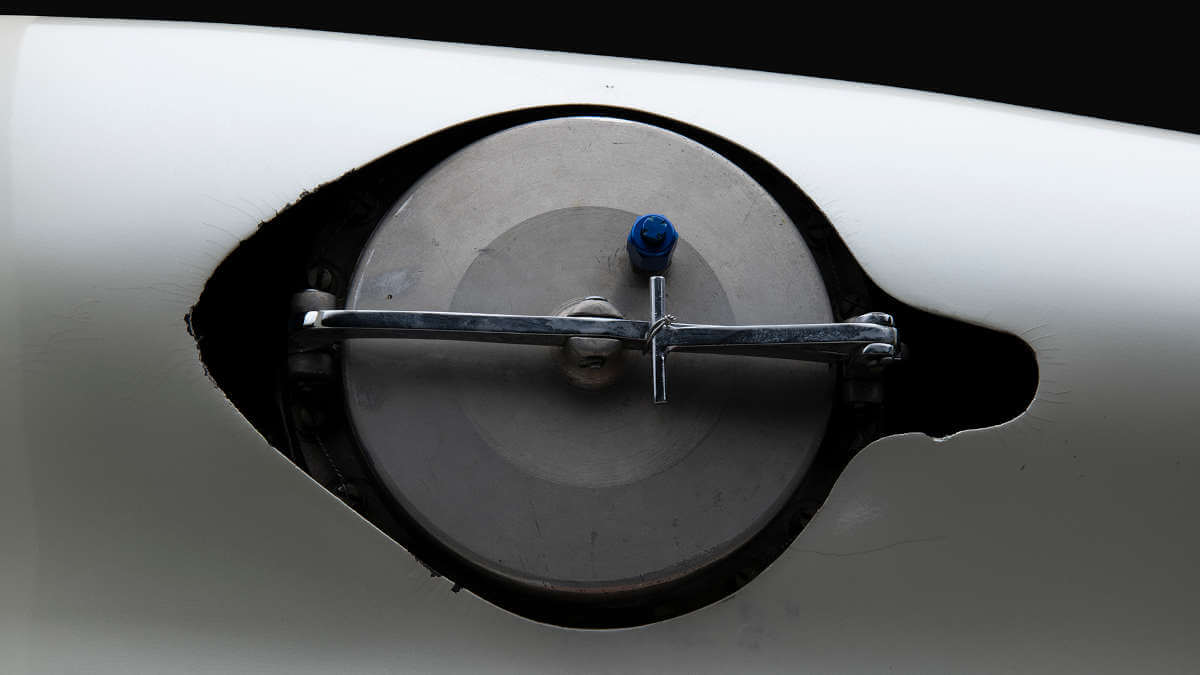

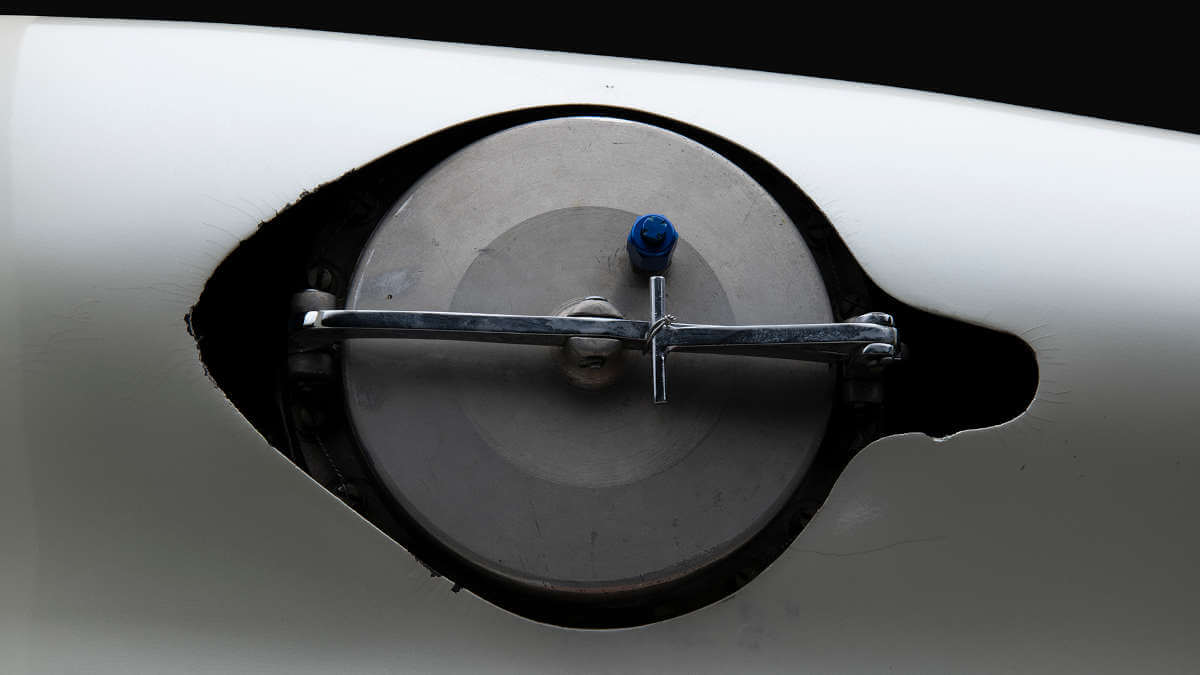

Floyd Trevis was a famous car builder who had a knack for putting together the best elements of a car to secure success. He made two key decisions. The first was to use the 255 cubic-inch Offenhauser inline four-cylinder engine with dual overhead camshafts, fuel injection and methanol fuel. At the time there was no other name than Offenhauser to be considered for a serious race team. The second decision was to replicate what was a proven design. He understood at this time, and for this project, forward progress wasn’t possible. With wisdom he built a direct copy of the car from designer A.J. Watson’s plans.

In today’s world and especially in the US, this would have filled years of court calendars in endless litigation. What it really reveals, is the character of a man, who without a doubt was one of the greatest race car designers of his time. When Watson was unable to fulfill or take on new contracts, he would simply loan out his designs and blueprints to his friends. In part the reason Bignotti hired Trevis, or most likely the whole reason.

The culture at Watson’s garage is a stark contrast from today’s contracted business world. Most of the people who worked on Watson’s cars worked for Lockheed and would come over after their day jobs and work on Watson’s car for the sole fact that it was A.J. Watson, never expecting payment. This was a carry over from his hotrod days in Glendale, where building was for the pure love of creating extraordinary machines.

Calling Watson’s cars “extraordinary machines” is putting it mildly. In the 1950s and 60s there was no other name that dominated the Indy 500. At times it seemed as though the whole field of 33 cars were either built by or had its origins from A.J. Watson.

Always a humble man, he never felt it necessary to be accredited for the wins of cars he didn’t build, but were built from his designs. This was the case in 1961 when A.J. Foyt won his first Indy 500 in the Trevis-Offenhauser built from Watson’s design. Partly it was because of who he was as a person, but on Gasoline Alley, everyone knew who was “The Man”. No words were needed because A. J. Watson “The Man” spoke through the power of his designs.

In this collection of images discover that powerful vernacular, that spanned the Indy 500 over two decades.

Trevis-Offenhauser – Details – by Matthias Kierse

Little is known about the Indianapolis 500 over in Europe. And if it is, most people only know that it is a counterclockwise oval race with a long tradition. Moreover, the “brickyard”, the start-finish line made of bricks, is quite famous. Its origin, on the other hand, is better known to US racing fans. In 1909, the entire race course in Indianapolis was made of crushed stones and tar. After various accidents due to the slippery road surface, they switched to bricks – 3.2 million bricks in total. The surface was correspondingly rough afterwards. Today, only the line at the level of the start and finish line remains, while the rest has long since been asphalted. In the early 2000s, an infield circuit was also built for Formula 1, using only Turn 1 of the four banked corners. However, the European top class of motorsports drove clockwise, which made Turn 1 the last corner before the start-finish straight.

1961, when A.J. Foyt competed in the Indy 500 in the Trevis race car designed by A.J. Watson and photographed by Bill Pack, was the last time they raced on the paved start-finish straight. A few months later, construction machinery arrived and asphalted this last area of the circuit as well – apart from the now famous strip. When you look at the comparatively narrow tires on the Trevis-Offenhauser, you really don’t want to imagine using them on changing surfaces from bricks to asphalt and back again twice a lap – at full speed in banked corners.

For the first time since 1949, the Indy 500 was no longer part of the Formula 1 World Championship calendar in 1961. Although it was only the 45th edition due to the war, the Indy 500 celebrated 50 years. Before the start, the first winner of the race, Roy Hardoun, who was 81 years old at the time, took a lap of honour in his 1911 Marmon Wasp. During qualifying practice, 25 drivers failed to qualify for the main race. This has been limited to a maximum of 33 participants for many years. Eddie Sachs was on pole position in 1961. The actual race favorite, Tony Bettenhausen senior, was killed during practice when the front axle of his race car collapsed.

As always, the actual race went over 200 laps to go the distance of 500 miles. Until the 94th lap, the lead kept changing between various drivers. Then A.J. Foyt and Eddie Sachs took the lead and fought out the race win among themselves. When Foyt headed for the pit lane on the 183rd lap to refuel, it looked as if Sachs would easily reel off the remaining race distance and win. But then a puncture on the right rear tire three laps before the end caused another change in the lead. Sachs had to settle for second place behind A.J. Foyt.

Unfortunately, another fatality occured on the 127th lap. Eddie Johnson had spun his race car in Turn 4 and hit the wall on the inside slightly. This caused a small fire, which a fire truck was dispatched to extinguish. One of the safety marshals sitting in the truck bed was John Masariu. During a turning maneuver, he apparently fell off and, tragically, was subsequently run over and fatally injured by the reversing fire truck.

There was also a novelty in the field of competitors that would be adopted by many teams in the following years and is taken for granted these days. Although the Indy 500 was no longer part of the F1 calender, Jack Brabham had imported a Cooper T51 from the UK and entered it for the race. Unlike all the other cars, this one already had a mid-engine layout with the engine behind the driver’s seat. Despite relatively low power, it managed a 13th place on the grid and ninth overall at the finish.

Authors: Matthias Kierse, Bill Pack

Images: © by Bill Pack