Automotive Art 29 – Duesenberg Indy

The name Duesenberg is well known even in Germany. No wonder, after all, the Duesenberg brothers came from the Lipperland region. They achieved their first racing successes in 1914. At the wheel was a later national hero, Eddie Rickenbacker. We tell some anecdotes of this era to the accompaniment of great pictures by Bill Pack.

Welcome back to a new part of our monthly Automotive Art section with photographer and light artisan Bill Pack. He puts a special spotlight onto the design of classic and vintage cars and explains his interpretation of the styling ideas with some interesting pictures he took in his own style.

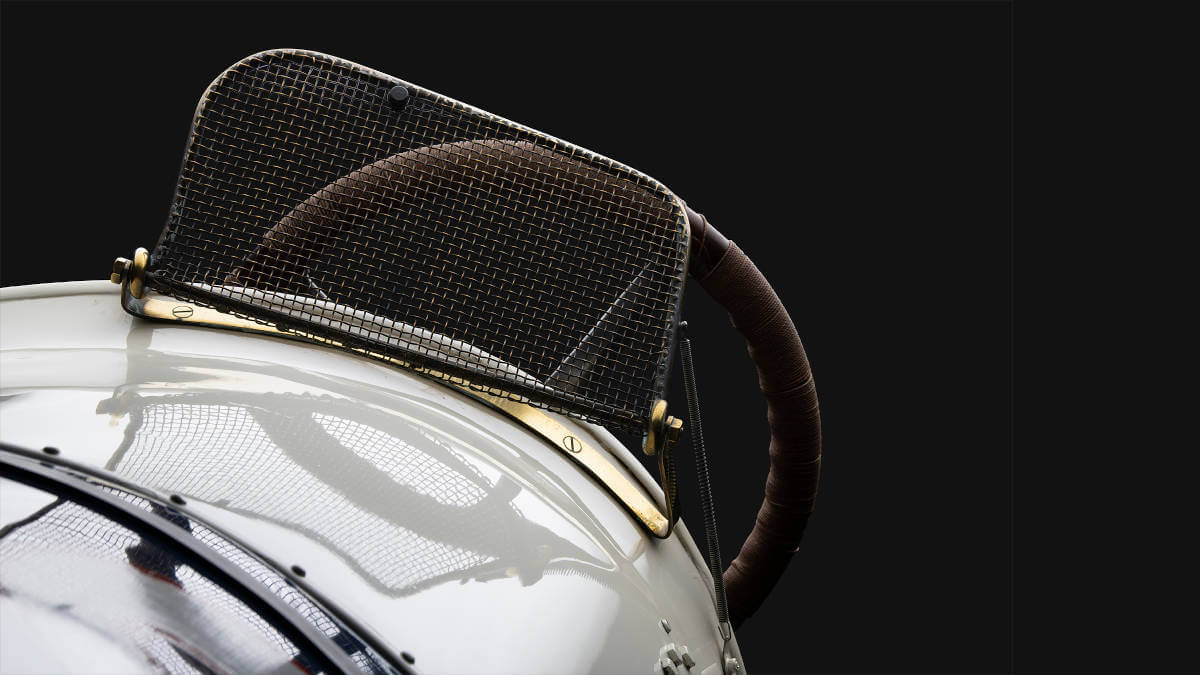

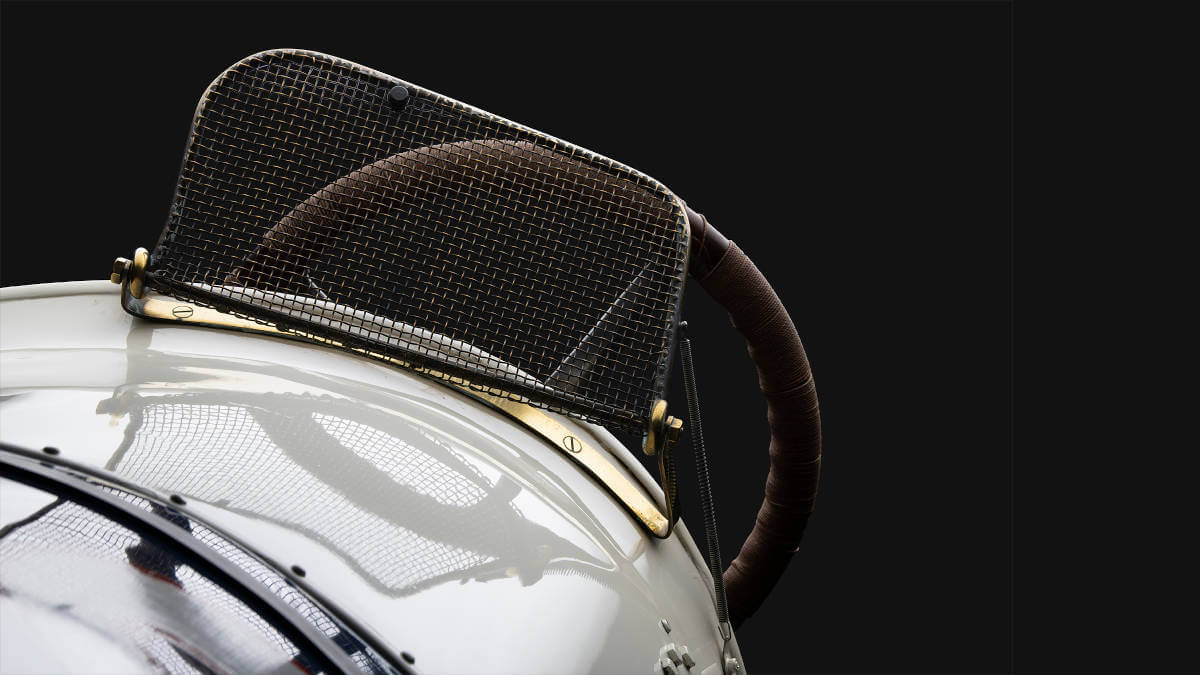

Into The Mind Of The Designer – by Bill Pack

It is easy to learn lots of facts and information about any automotive designer. We learn what great shops they worked for, what model of cars they designed and the innovations they have brought to the industry. We know about them, but we do not know them. With my imagery I attempted to get into the soul and spirit of the designer. By concentrating on specific parts of the car and using my lighting technique, I attempt to highlight the emotional lines of the designer.

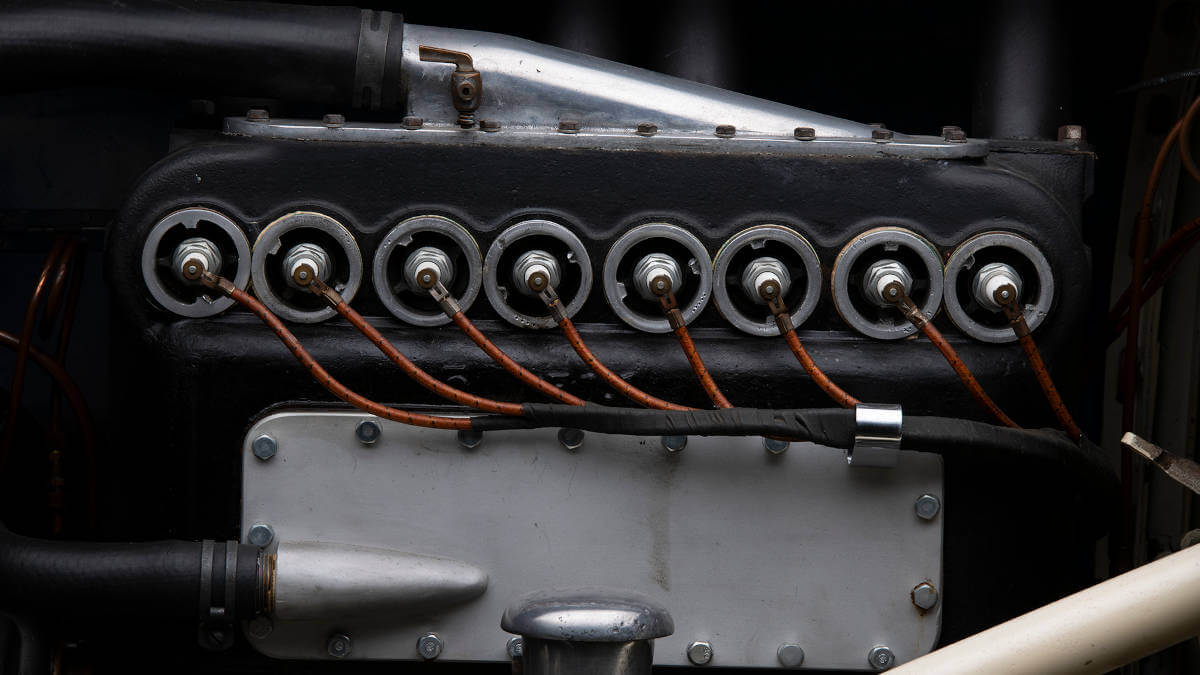

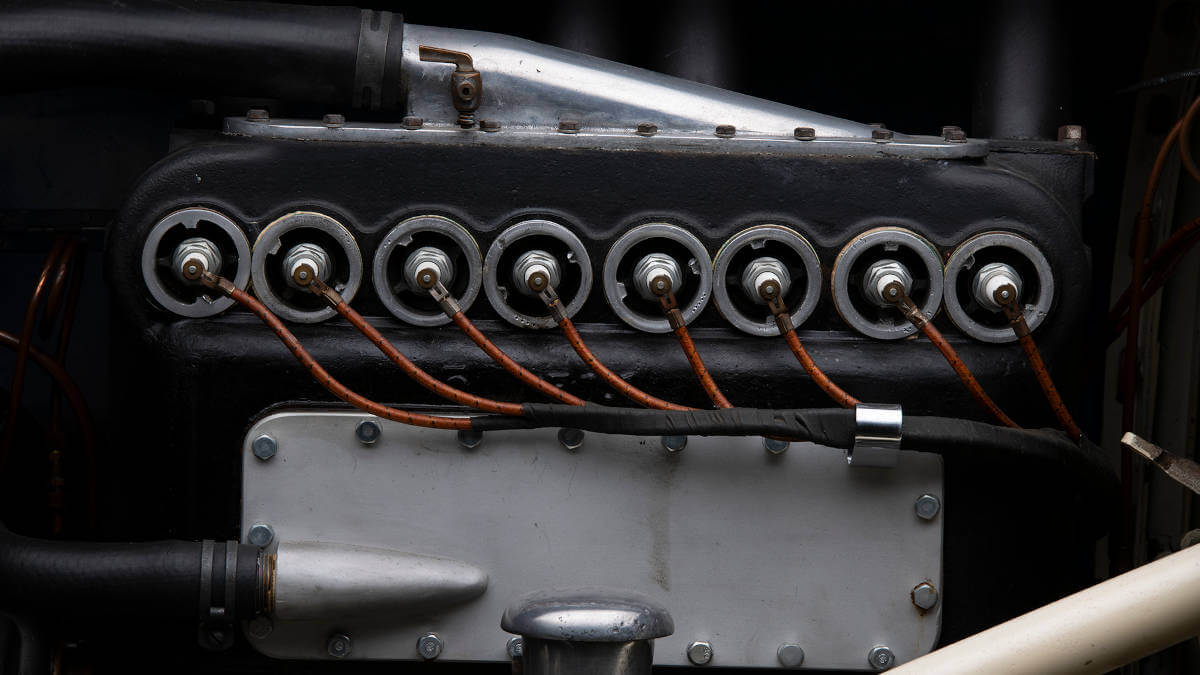

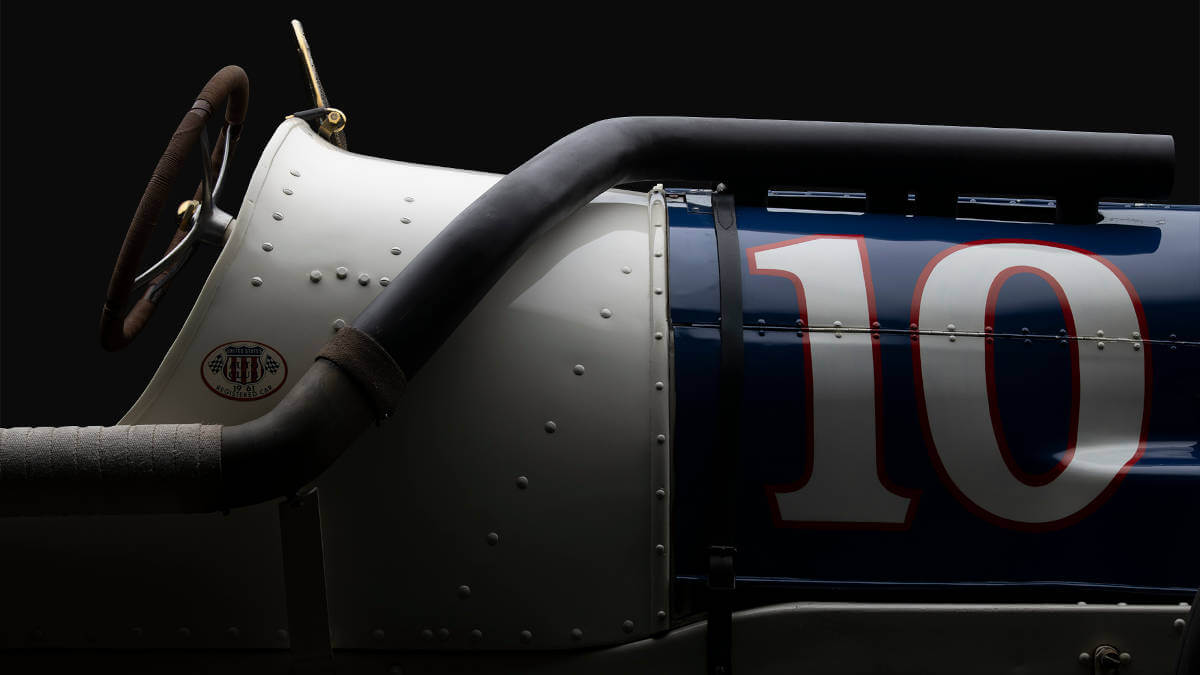

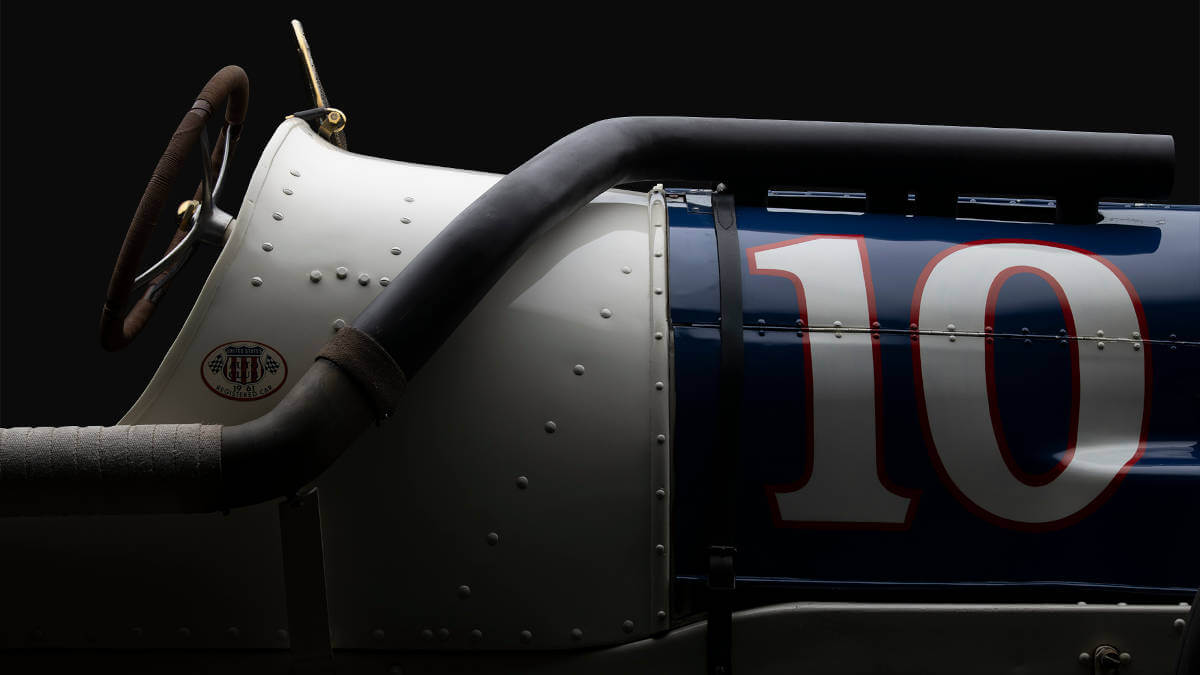

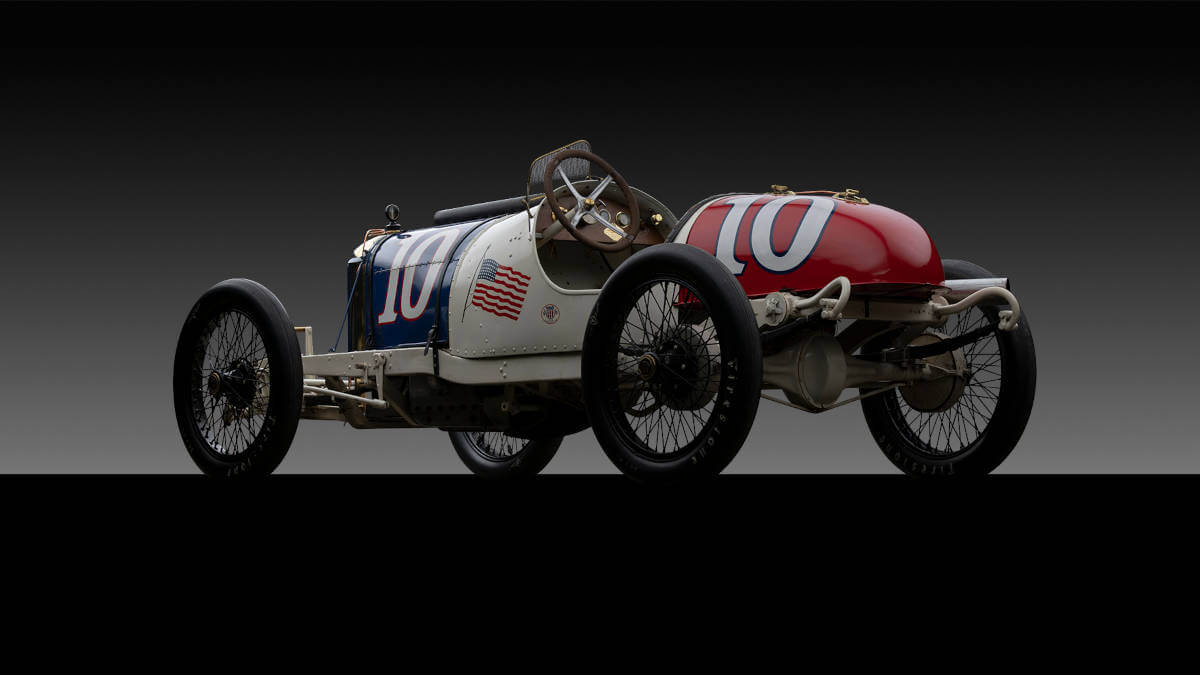

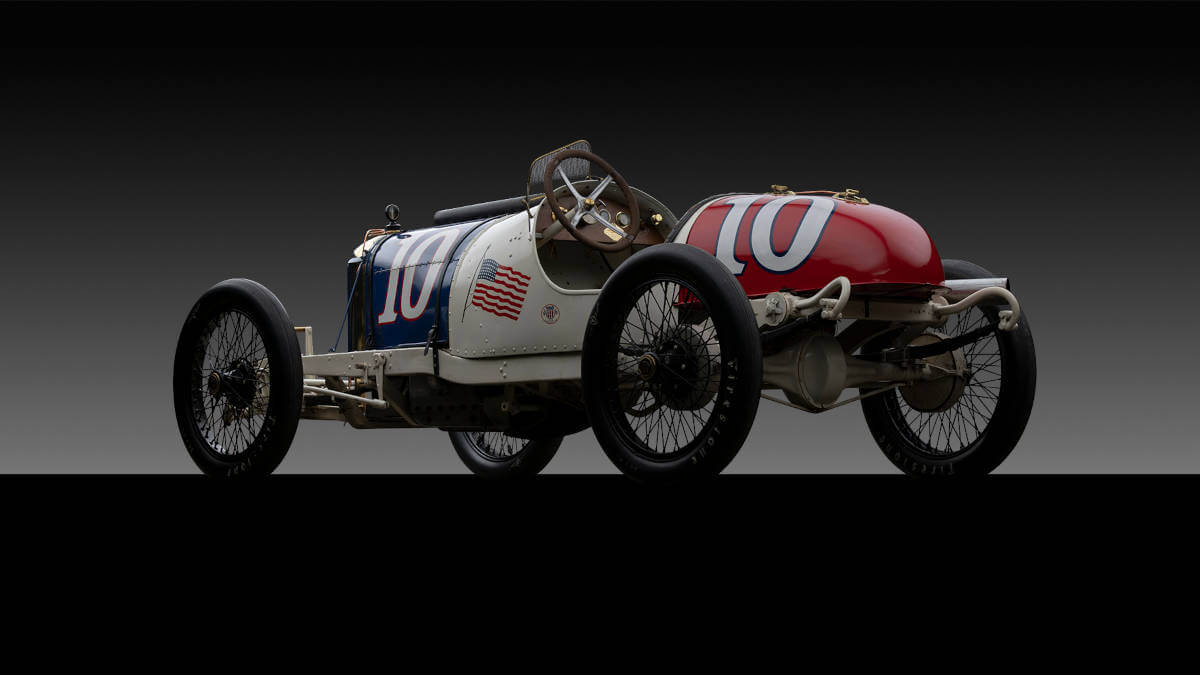

1914 Duesenberg Rickenbacker Indy – Designed by Fred and Augie Duesenberg

A Moveable Feast – I have had the rare privilege of being commissioned by the Phoenix Art Museum to travel the United States and create my Automotive Art Imagery for the exhibition, “Legends of Speed”. This exhibition ran through March 15, 2020 and featured 22 iconic race cars. It spanned the years 1911 through 1978.

Each car has been driven in significant races by iconic drivers. From Sir Stirling Moss to Dan Gurney and Mario Andretti, racing from Le Mans, Indianapolis 500 to the Italian Gran Prix and many more. The history is rich and storied.

My part of the story was a twelve thousand mile Gran Turismo that took me to all four corners of the Unites States into some of the most coveted and significant private collections in the world.

One of these destinations was at the “Brickyard” where I spent the day with the brothers creation, the 1914 Duesenberg Rickenbacker Indy.

The scheduling for the Grand Tour around America was by careful planning and design. However what was not factored in was the date we arrived in Indianapolis to photograph the Duesenberg. It happened to be the testing week at the Indy 500. We spent two days at the famous track creating imagery of three iconic Indy cars for “Legends of Speed”, while testing for the weekends time trials was in progress. The engine notes of the modern Indy cars were reverberating throughout the space as I was creating imagery of iconic cars of Indy’s past. It is an experience I will never forget.

Fred and Augie immigrated from Germany in the mid 1880s to the small town of Rockford, Iowa. With no formal training, but a natural sense of how things worked, Fred began working on farm equipment and windmills. The brother’s journey towards cars was through bicycles and motorcycles. True to hallmark of German design, the brothers priced efficiency and practicality. They complemented each other, Fred had the head for design and Augie had the business sense and the craftsman eye.

The brothers almost qualified for the Indy 500 on their first try in 1912 with a Mason badged four-cylinder engine. They then left Iowa in 1913 and moved to Minnesota setting up the Duesenberg Motor Company. Fred’s natural ability as an engineer was said to even be beyond that of Harry Miller which we featured in Automotive Art 22, which is high praise indeed.

The story gets an infusion of texture and fame when Eddie Rickenbacker became their factory driver in 1914 for the Indianapolis 500. They finished tenth in this race, but the fame began with the next race, a 300-mile race at Sioux City, Iowa on Independence Day 1914.

With a crowd of 42,000, Rickenbacker got off to a good start, by the 20th lap he was in third. By the 30th lap he was in second with only 17 seconds separating him from the leader Spencer Wishart. They were neck and neck throughout the rest of the race. Wishart had a bad pitstop and Rickenbacker took the lead. Eddie realized he was low on oil with 5 laps to go. He turned to inform his mechanic but found him to be unconscious with a big brush forming on his forehead. Not knowing if he had survived or not Rickenbacker reached over his mechanic and pumped the oil himself. They finished the race a mere 48 seconds ahead of Wishart. The mechanic woke up in the pits finding out they had won the race.

The win in Sioux City cemented Rickenbacker reputation as a driver and began a illustrious auto-racing history for Fred and Augie. In these curated images, discover the early design of Fred and Augie that became the legend of Duesenberg.

Duesenberg Rickenbacker Indy – Details – by Matthias Kierse

Nowadays, it sounds unimaginable to have a co-driver in the car at a speedway race. Whether you look at the current Indy Car or Nascar series, it’s always single-seater racing cars. Before World War 1, it was a different story. As can be seen in the text portion of Bill above, Edward ‘Eddie’ Vernon Rickenbacher (he didn’t have the spelling changed to Rickenbacker until 1917) had a mechanic with him for his first major victory as well as shortly before at the Indy 500. This was necessary because at that time there were neither electric gasoline nor oil pumps. Instead, the ‘Schmiermaxe’ (lubricating Max), as he was fondly called in the German-speaking world, had to ensure by hand that enough lubricant reached the engine. In races on winding terrain, he also served as a counterweight for the driver and sometimes had to lean far our of the moving car.

It all sounds a bit like times long gone. For some readers of the lines, even the 1914 Duesenberg migh simply be an ancient car that you might leave unnoticed in a museum. However, it is precisely these vehicles that sometimes tell highly exciting stories. One of them is the race in Sioux City on July 4, 1914, the American Independence Day. At the time, Duesenberg entered two cars that had already been painted in the colors of the American flag for the Indy 500 shortly beforehand and also displayed this flag on the side of the hood. Alongside Rickenbacker, a driver named Alley drove the second car. During a pit stop, this Duesenberg caught fire briefly, slightly injuring Alley in the face. Rather than retiring this car, Duesenberg accepted the offer of a competitor. Ralph Mulford had actually started with a Peugeot, but had had to park it shortly before with engine failure. As he had been a works driver for Duesenberg in the previous year, he knew the team well and now offered to continue driving the only slightly damaged car. In the end, he finished third.

In fact, the young Duesenberg car brand wasn’t doing particularly well financially in mid-1914. Shortly before the race in Sioux City, an important investor withdrew. This left the company with its back to the wall. However, the victory of Eddie Rickenbacker in combination with third place by Alley and Mulford brought in prize money of US$ 12,500, which was a large sum at the time. In addition, there were non-cash prizes and, of course, the trophies, which could be used for promotional purposes.

Normally, the Indianapolis 500 race takes place around Independence Day. In 1914, however, this date was relinquished to Sioux City, where the new speedway with a length of around two miles was inaugurated with this race. While European manufacturers such as Peugeot showed off and took victories at the Indy for the first time in that era, most of these cars dropped out early at Sioux City. This allowed American brands to shine on this important national holiday.

In the early laps, Bob Burman was in the lead. After a tire blowout, he lined up again in fourth place and offered his competitors a decent fight for positions. However, experts had already predicted before the race that his car wouldn’t last the distance. And so it came to pass. Engine problems caused a retirement. Thus Wishart in a Mercer took the lead ahead of Mulford (still driving the Peugeot at this point) and Barney Oldfield in a Stutz. Eddie Rickenbacker took a more cunning approach to the 300-mile race. He didn’t drive at the limit, preferring to set consistent lap times. As a result, he constantly worked his way forward and benefited from the defects of his faster rivals. Oldfield, for example, also retired with engine failure after 100 miles.

At the 200-mile mark, Rickenbacker was already in front, followed by Wishart and Mulford, who was meanwhile driving the second Duesenberg. After his final pit stop, Eddie Rickenbacker finally let his race car off the chain and showed the potential of the design by setting top lap times. After he had crossed the finish line as the winner, his interest was entirely focused on his personal mascot. For several races, a cat followed him wherever he went.

In later years, Eddie Rickenbacker became a flying ace in the United States Air Force during World War 1. This came about through a contract with the British Sunbeam racing team for the 1917 season, which took him to the parent plant in Wolverhampton. Even before he left the US, he was joined by two agents from Scotland Yard, who kept tabs on him until he returned to the United States. The reason for this was a falsely researched article in the Los Angeles Times in 1914, in which Rickenbacker was described as the disinherited son of a Prussian baron. Since the UK was at war with the Prussians, they didn’t want to get a spy into the country and therefore took no chances with Rickenbacker. He, on the other hand, saw Royal Flying Corps planes in the air above his hotel and decided that if the USA would enter the war, he too would be a pilot.

His idea of training race car drivers and mechanics to become pilots and co-pilots was ignored by the military. They preferred to have educated college graduates in the flying squadrons. Rickenbacker did eventually acquire flight training while in the military in France and shot down five enemy aircraft in the first month, promoting him to a flight ace. As leader of the 94th Squadron, he provided more victories and a previously unknown sense of teamwork among the pilots. Although he officially left the Army as a major, he always used his rank as captain, which he felt was more appropriate.

After attempting to fly nonstop across the USA four times, he sought new fields of endeavor. Together with Ray McNamara, he introduced the first Rickenbacker automobile in New York in 1922. However, his car brand only lasted until November 1924. Three years later, Eddie Rickenbacker acquired the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Over the next decade and a half, he provided modernized buildings around the course and other improvements. In 1941, the last Indy 500 before World War 2 took place. Eddie was forced to close his beloved circuit because further racing events would have consumed fuel, rubber and other materials necessary for the war efforts. Four years later, he sold the property to Anton Hulman junior.

These are just a few stages in the life of Eddie Rickenbacker. An enterprising businessman, he was involved in many companies, often serving in executive positions, and was also well connected to General Motors through his marriage. He narrowly survived a plane crash in 1941, wrote the story for a comic book popular in the US, and finally survived an emergency ditching of a military plane in the Pacific in 1942. He also visited the Soviet Union while World War 2 was still in progress and brought back important insights to the West. On July 23, 1973, he died in Zurich, Switzerland, after suffering a stroke followed by pneumonia. He had actually traveled there to seek health support for his wife. She took her own life four years later to follow her husband.

Authors: Matthias Kierse, Bill Pack

Images: © by Bill Pack