Automotive Art 27 – Franklin Model D

This time, the Automotive Art Feature takes us far back into American automotive history. In 1911, the Franklin took off on an endurance race from Los Angeles to Phoenix. There were hardly any roads in today’s sense. Much of the racing took place on dirt and farm roads as well as in the desert.

Welcome back to a new part of our monthly Automotive Art section with photographer and light artisan Bill Pack. He puts a special spotlight onto the design of classic and vintage cars and explains his interpretation of the styling ideas with some interesting pictures he took in his own style.

Into The Mind Of The Designer – by Bill Pack

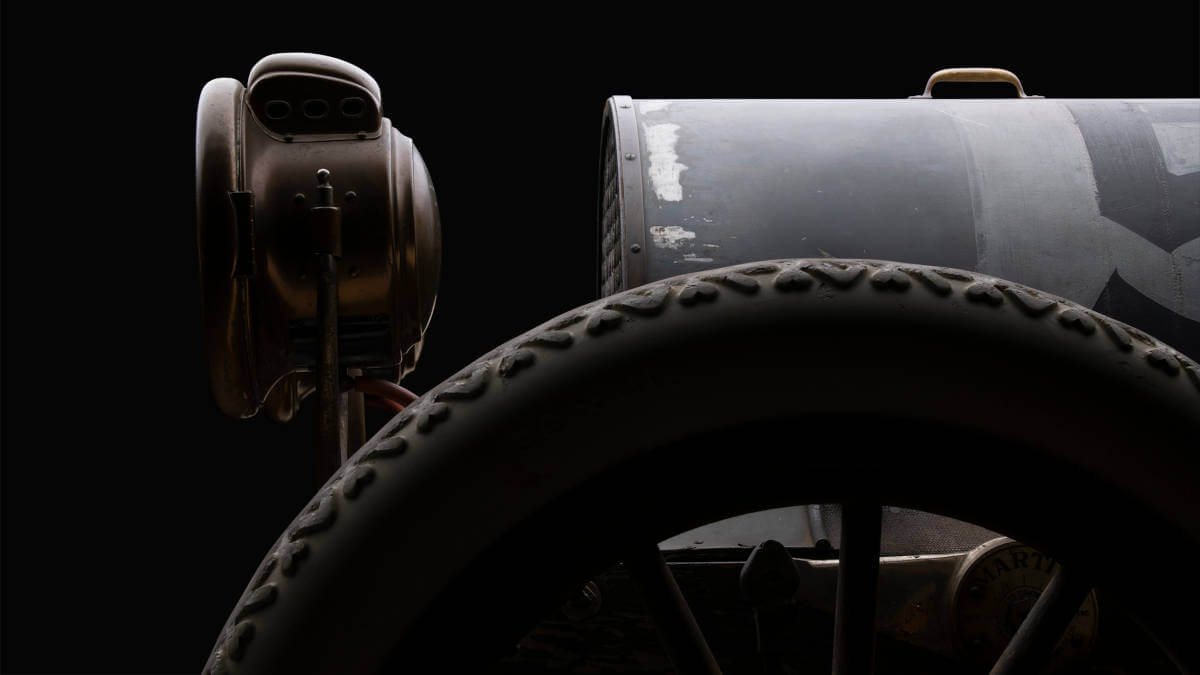

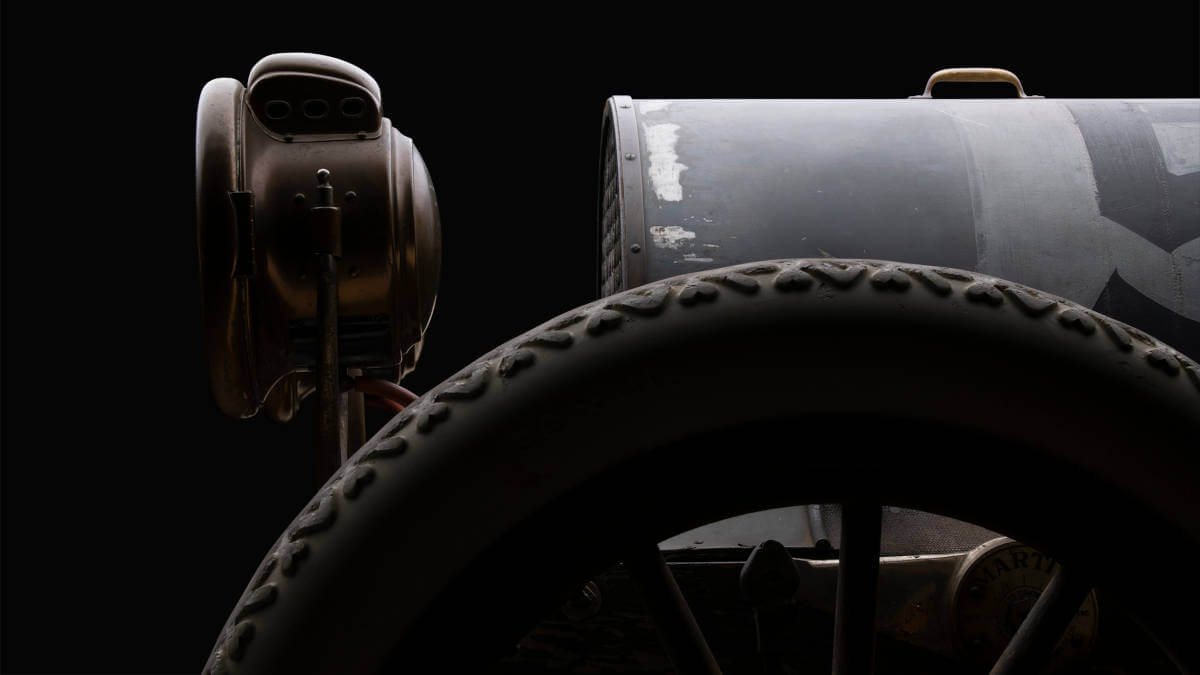

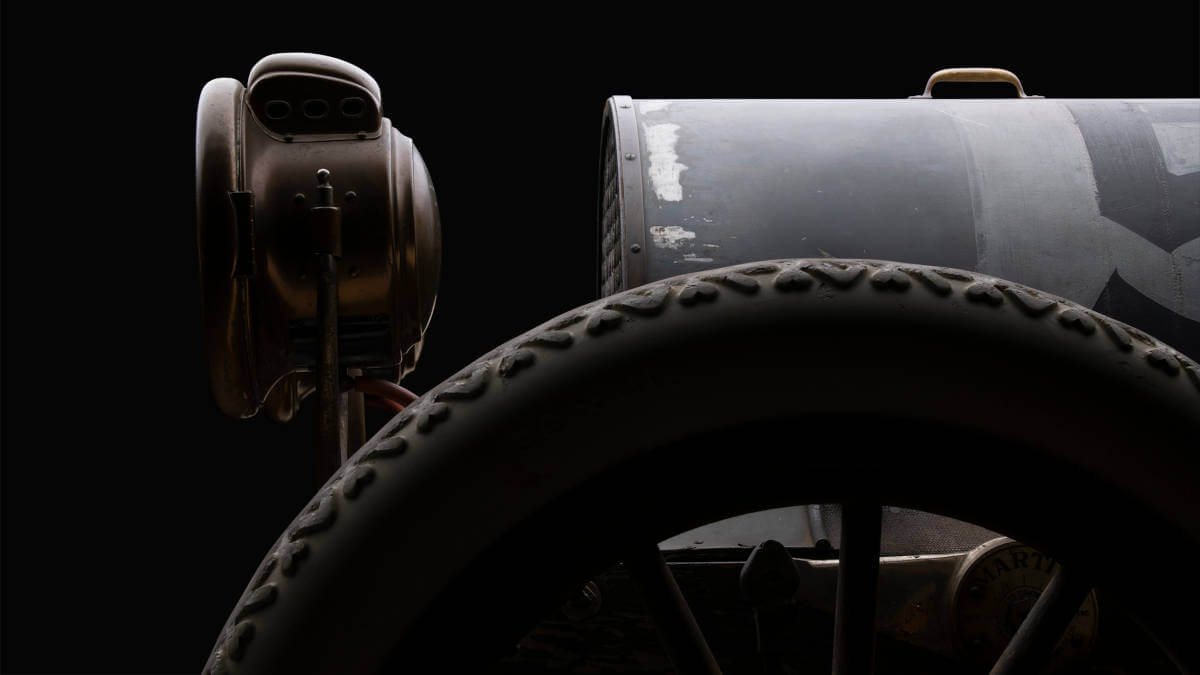

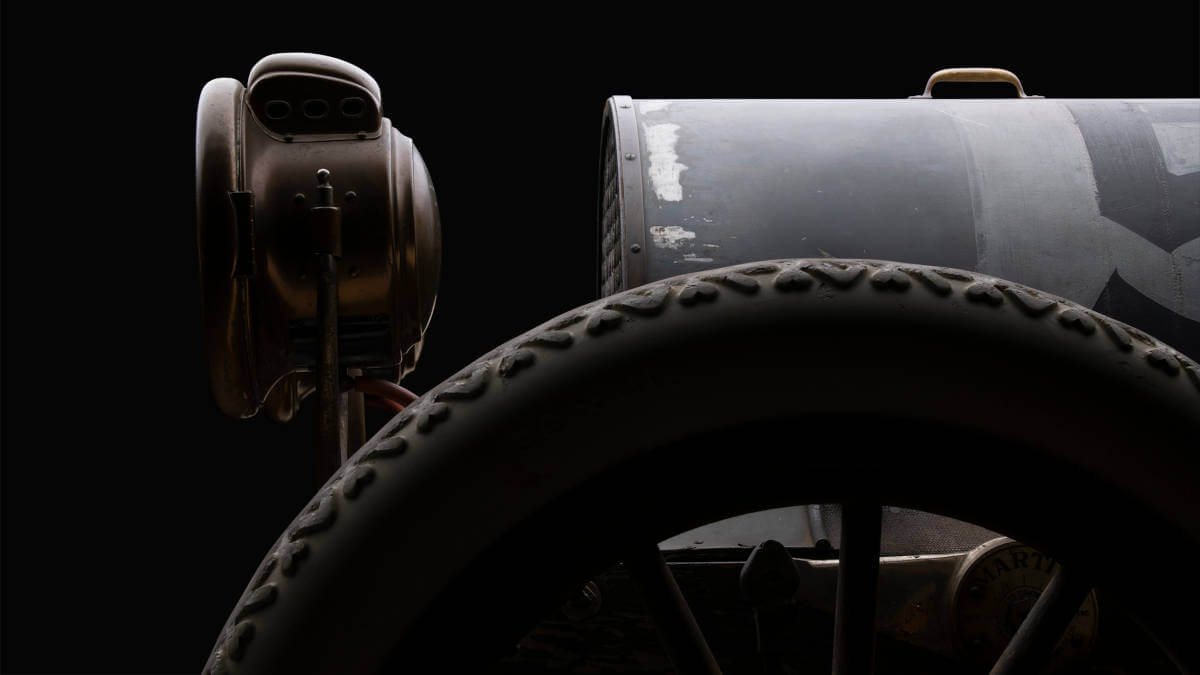

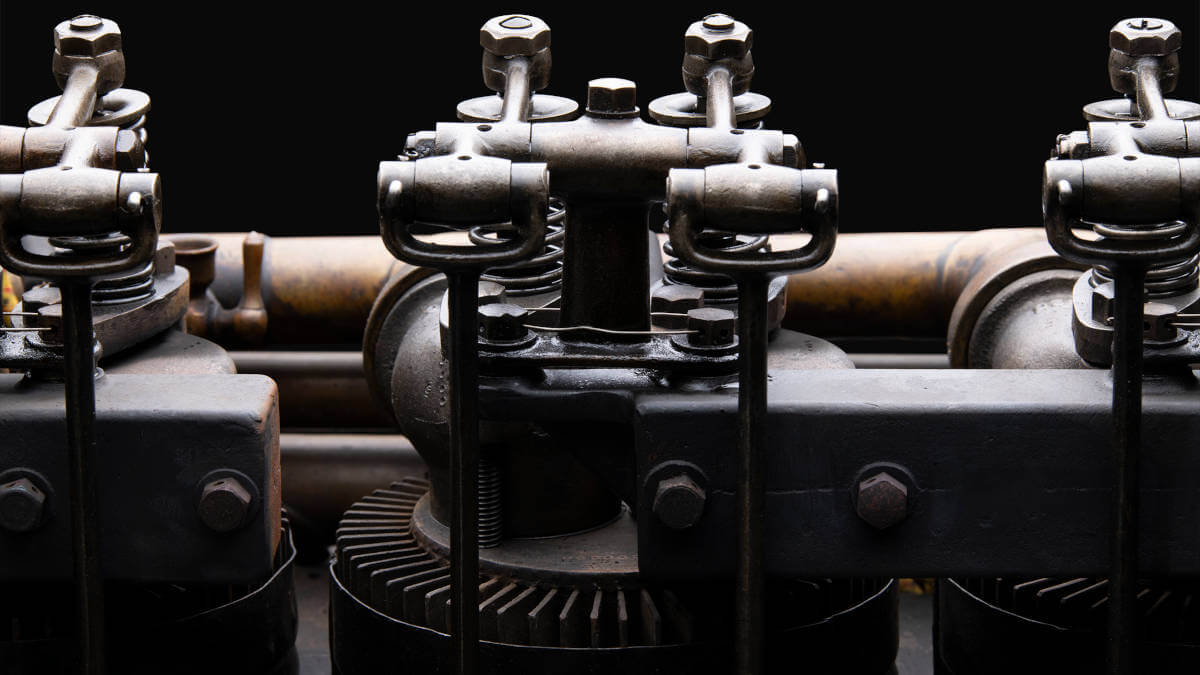

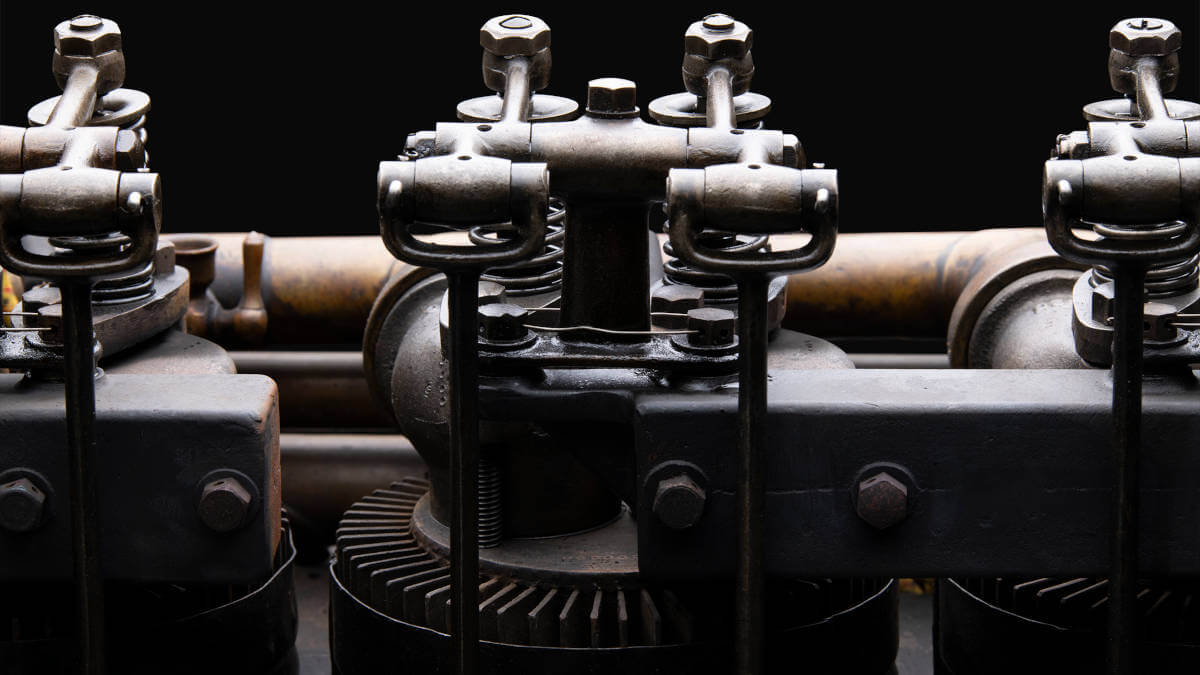

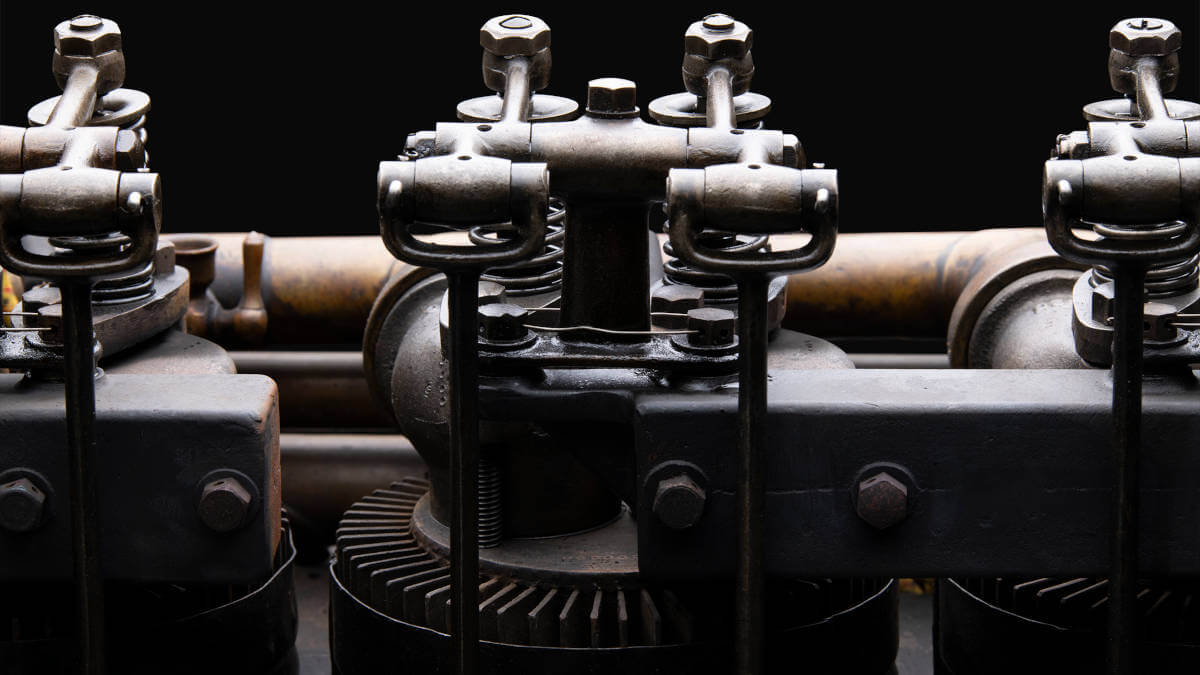

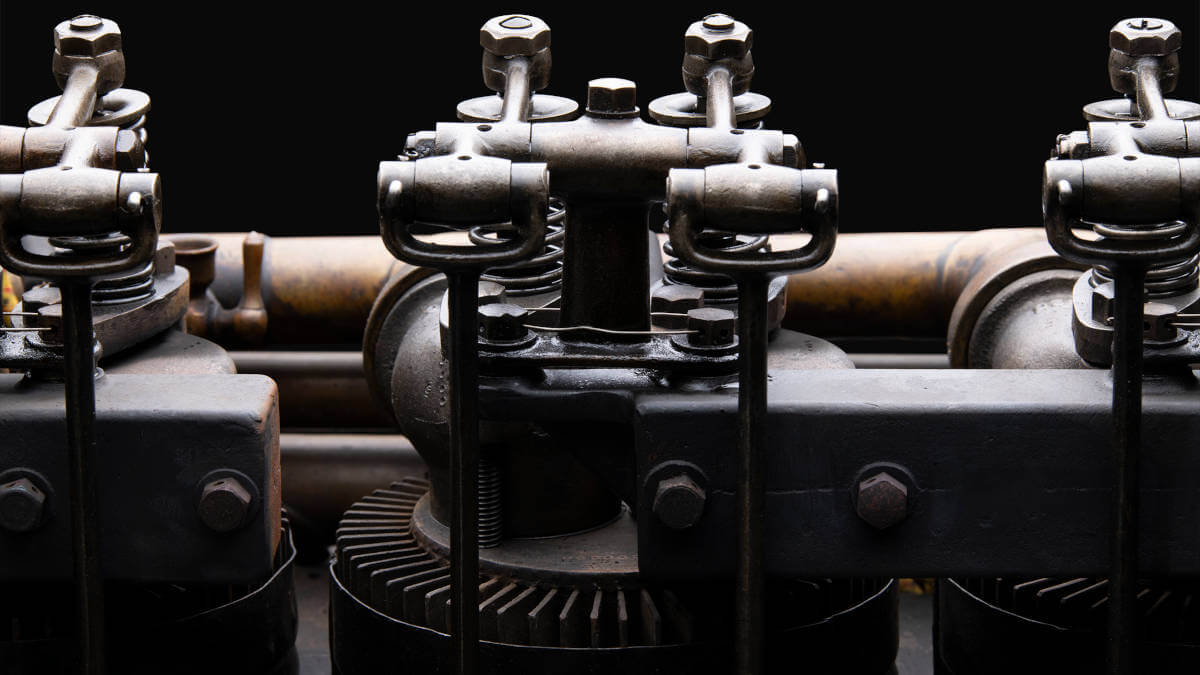

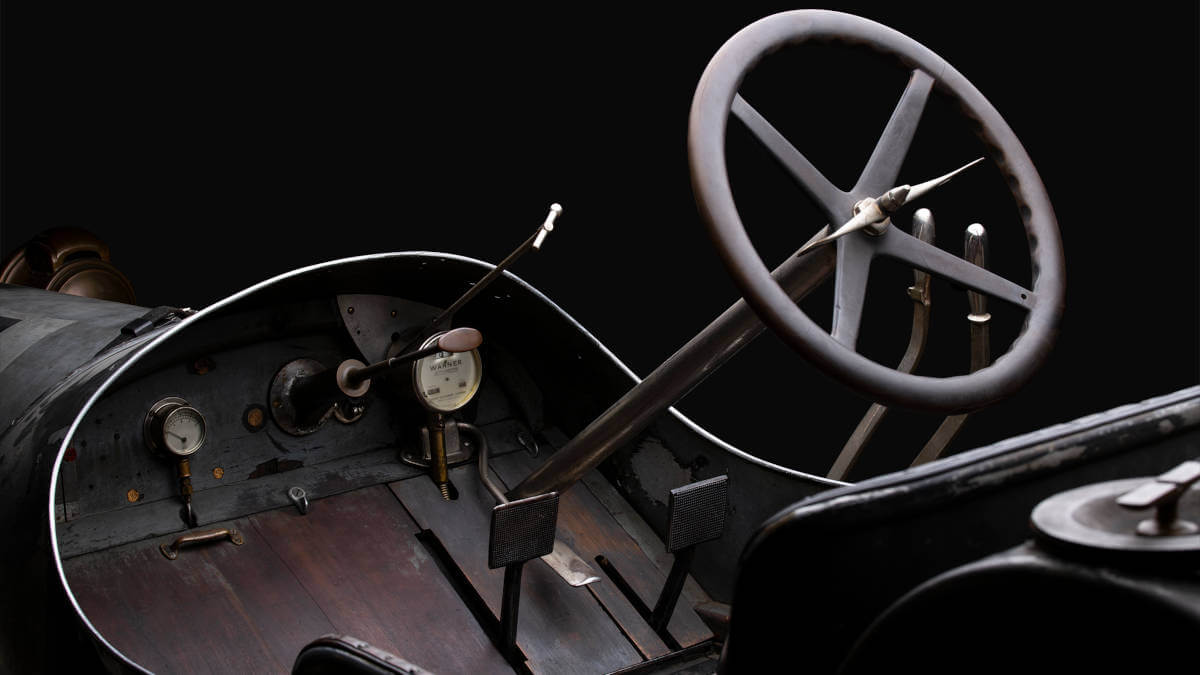

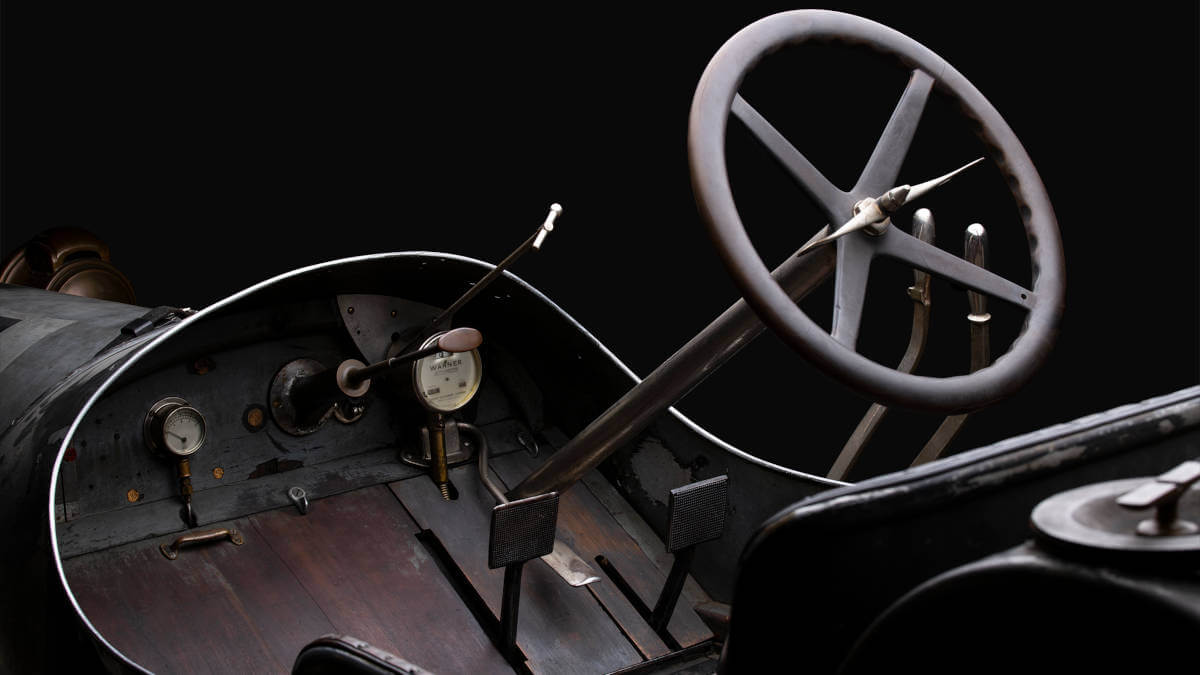

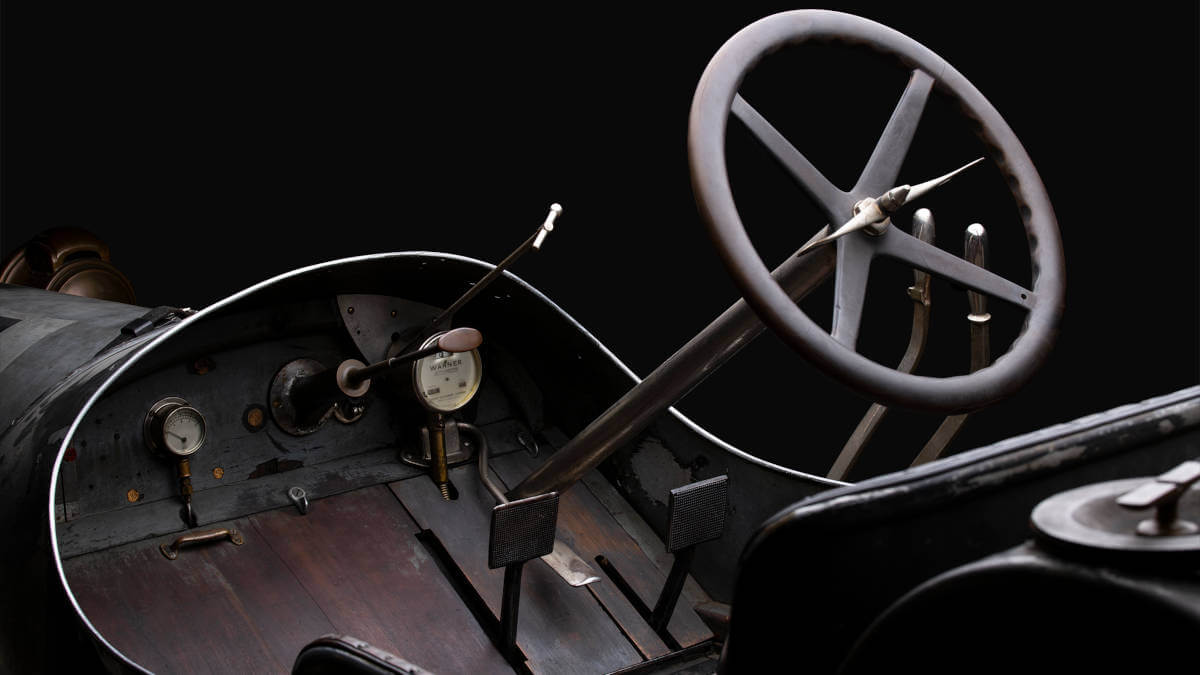

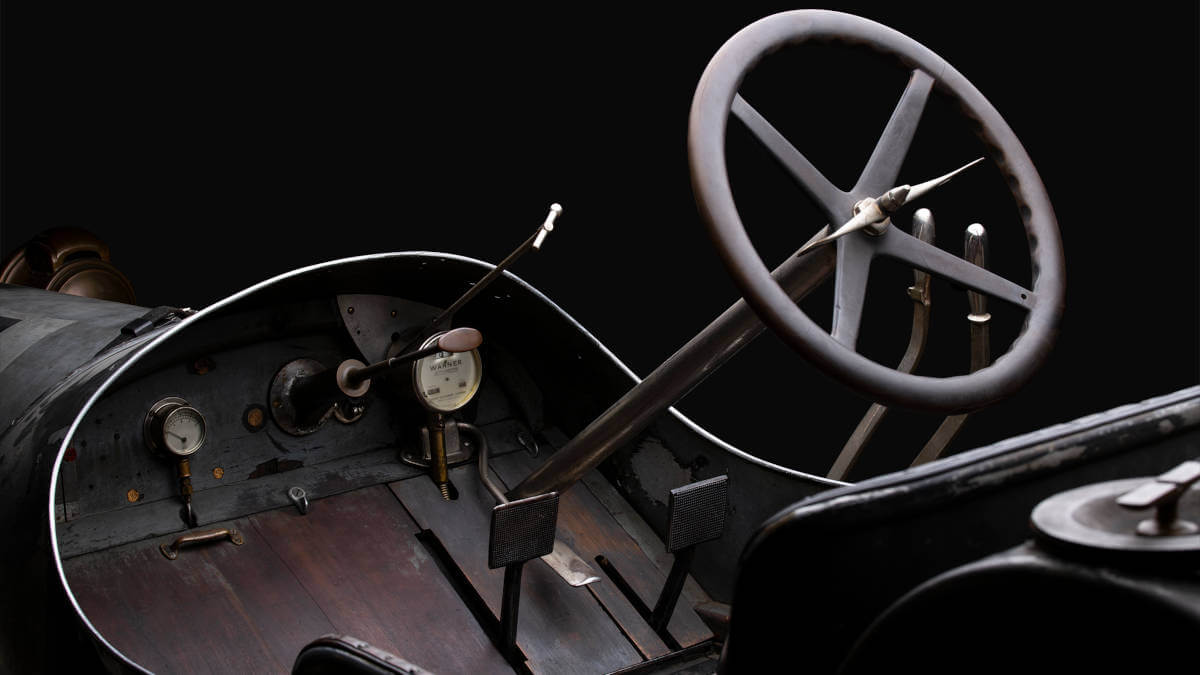

It is easy to learn lots of facts and information about any automotive designer. We learn what great shops they worked for, what model of cars they designed and the innovations they have brought to the industry. We know about them, but we do not know them. With my imagery I attempted to get into the soul and spirit of the designer. By concentrating on specific parts of the car and using my lighting technique, I attempt to highlight the emotional lines of the designer.

1911 Franklin Model D – Designed by H.H. Franklin and John Wilkinson

A Moveable Feast – I have had the rare privilege of being commissioned by the Phoenix Art Museum to travel the United States and create my Automotive Art Imagery for the exhibition, “Legends of Speed”. This exhibition ran through March 15, 2020 and featured 22 iconic race cars. It spanned the years 1911 through 1978.

Each car has been driven in significant races by iconic drivers. From Sir Stirling Moss to Dan Gurney and Mario Andretti, racing from Le Mans, Indianapolis 500 to the Italian Gran Prix and many more. The history is rich and storied.

My part of the story was a twelve thousand mile Gran Turismo that took me to all four corners of the Unites States into some of the most coveted and significant private collections in the world.

One of these destinations was in prairie lands of the US where I spent the day with a creation by H. H. Franklin and John Wilkinson, the 1911 Franklin.

I must admit that my eye is drawn towards the stylistic lines of Giorgetto Giugiaro, Pietro Frua, Malcolm Sayer, Franco Scaglione and Sergio Scaglietti to name a few. Most people are drawn to a type of art, music and cars, generally from a certain decade in their life. This car and its story told to me by the owner changed that for me.

When I hear the term ‘air cooled engine’, Porsche comes to mind. When I hear the term ‘endurance racing’, I think of Le Mans. For ‘off road racing’ it is the Baja 1000. The roots for all of these iconic races and innovations reside in this one race car from the early part of the 1900s. The short story is in 1901 John Wilkinson, the engineer inventor of the first self-starter for an automobile, built an air-cooled engine for a car. He then met H. H. Franklin who at the time made die-cast cars. The H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company with Wilkinson made the bold pivot to building actual cars.

Part two of the story takes place in Los Angeles with the renowned Southern California Franklin distributor Ralph Hamlin, who excelled as a promoter. “It was not easy to sell air cooling,” he wrote in ‘Five Years on the Desert’, “my competitors, all of whom sold water-cooled cars, would tell my prospects that if air cooling was so good, the rest of the cars would be using it.” So as promoters had been, if not since time immemorial, then at least for a few years, he decided to race the car to prove it. “I entered any event that came along. When the desert race was suggested, it was my chance to put air cooling on top, if I could win.” And win he did.

He was not only an early supporter of the air cooled cars in general, but also in automotive endurance. How better to promote endurance and sell cars than an endurance race. The Desert Race was a 500-mile road race from Los Angeles to Phoenix. Believed to be the most grueling race in American history, it consisted of 80 miles of dirt roads and 420 miles of stagecoach or cattle trails.

Tamlin teamed up with Earle Anthony, a famous Packard dealer; and John Bullard, the attorney general for the Territory of Arizona and president of the Maricopa Automobile Club, as the originators of the derby. Hamlin and Anthony organized the Motor Car Dealers Association and worked with Bullard to organize the first Desert Race in 1908. Hamlin and Anthony sought to prove the reliability of automobiles, while Bullard’s motivation was to promote the need for better roads.

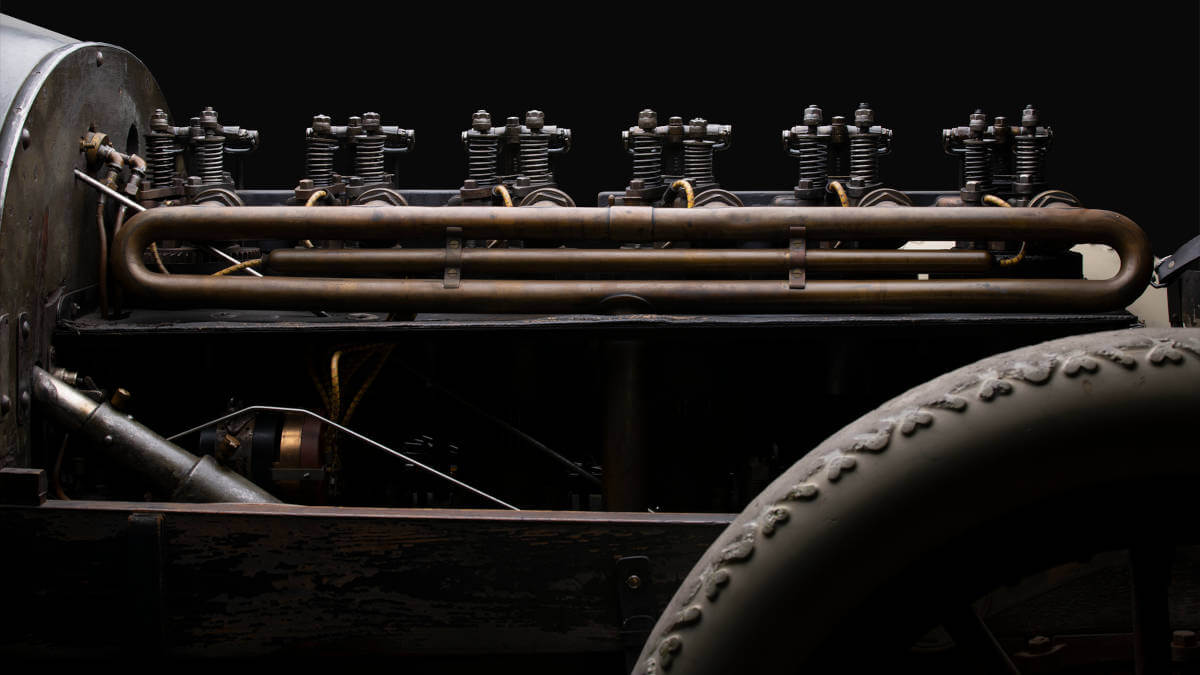

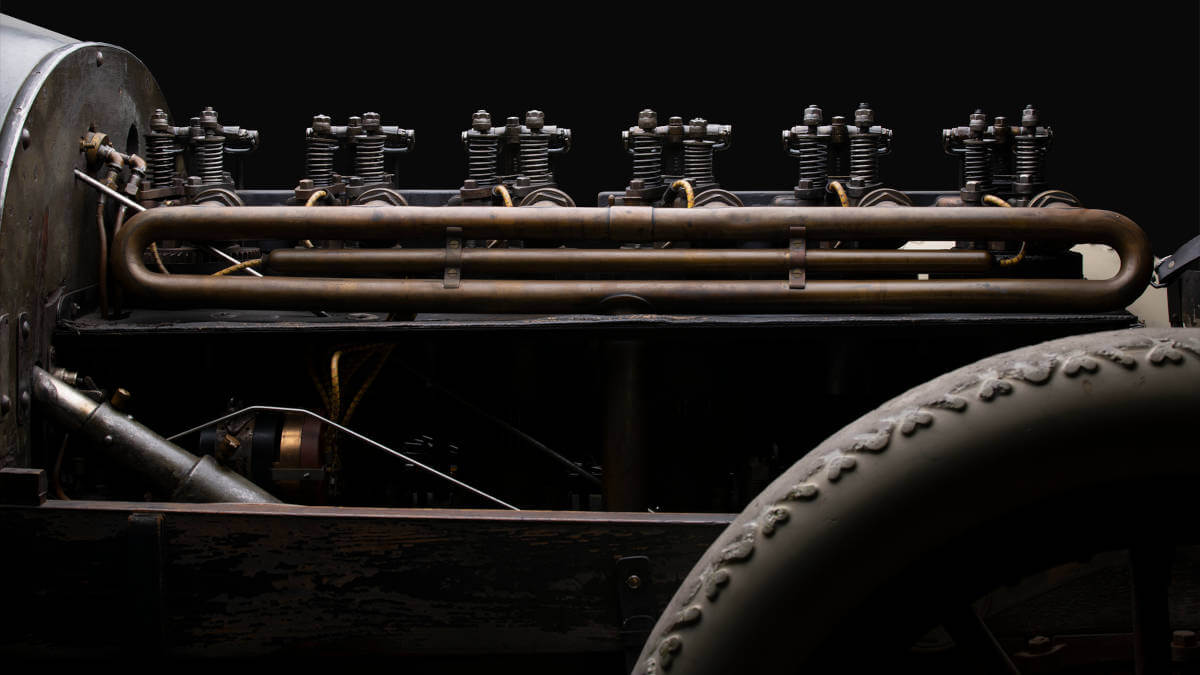

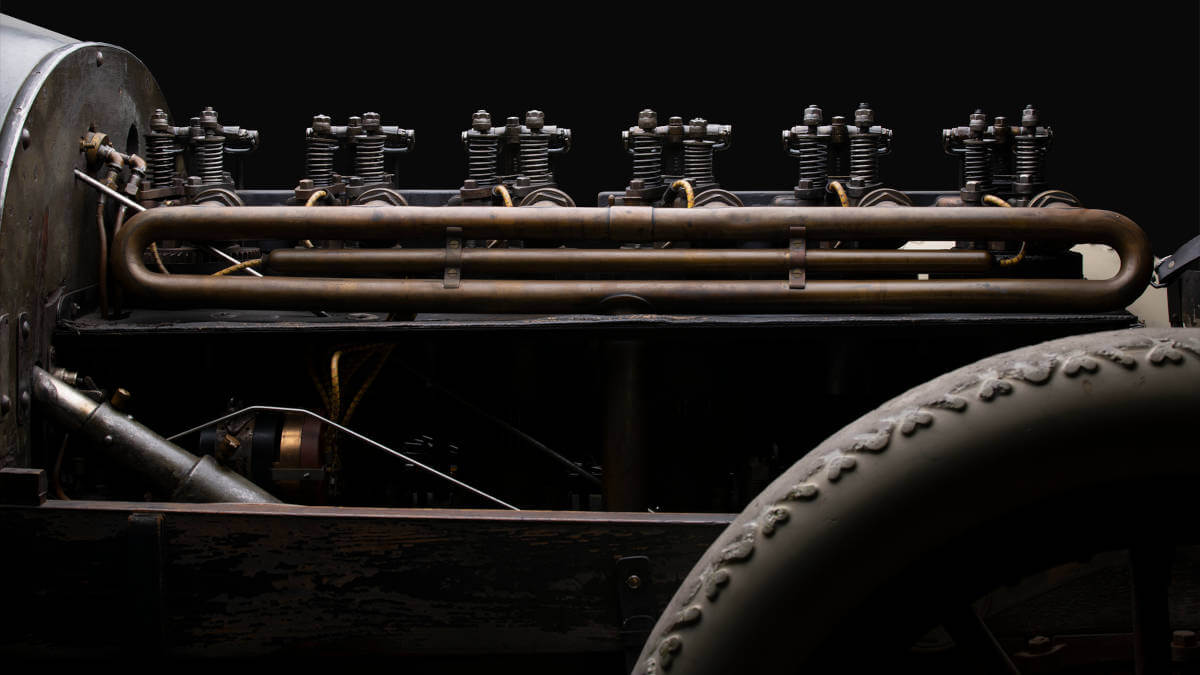

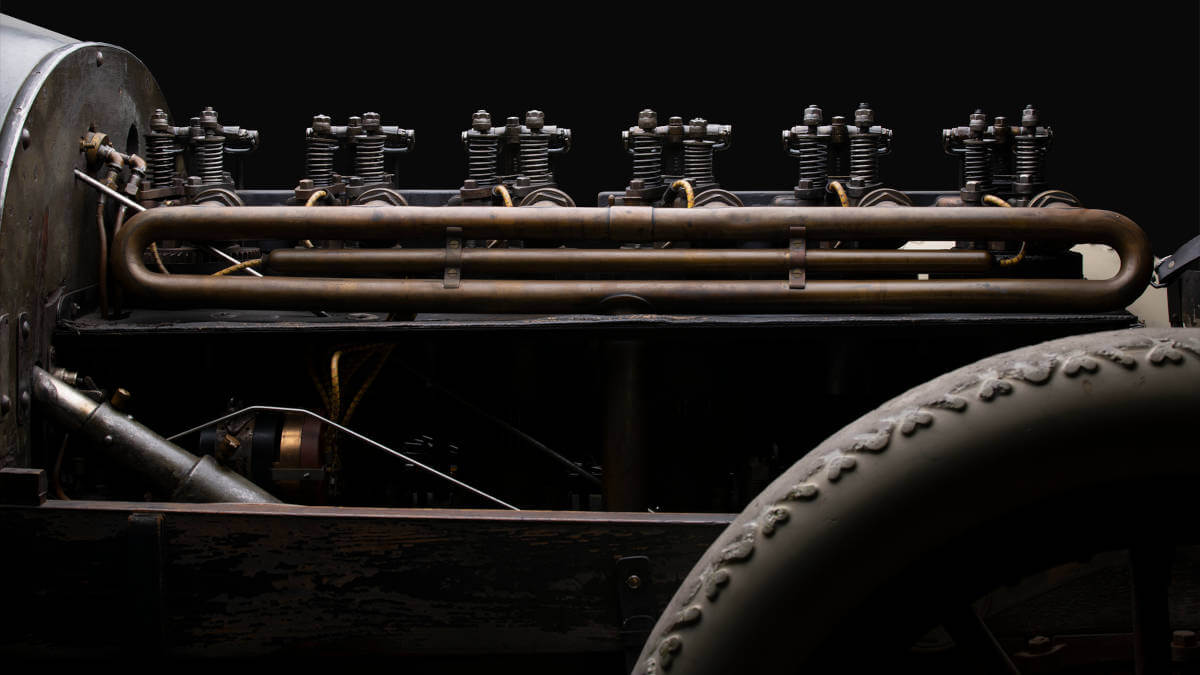

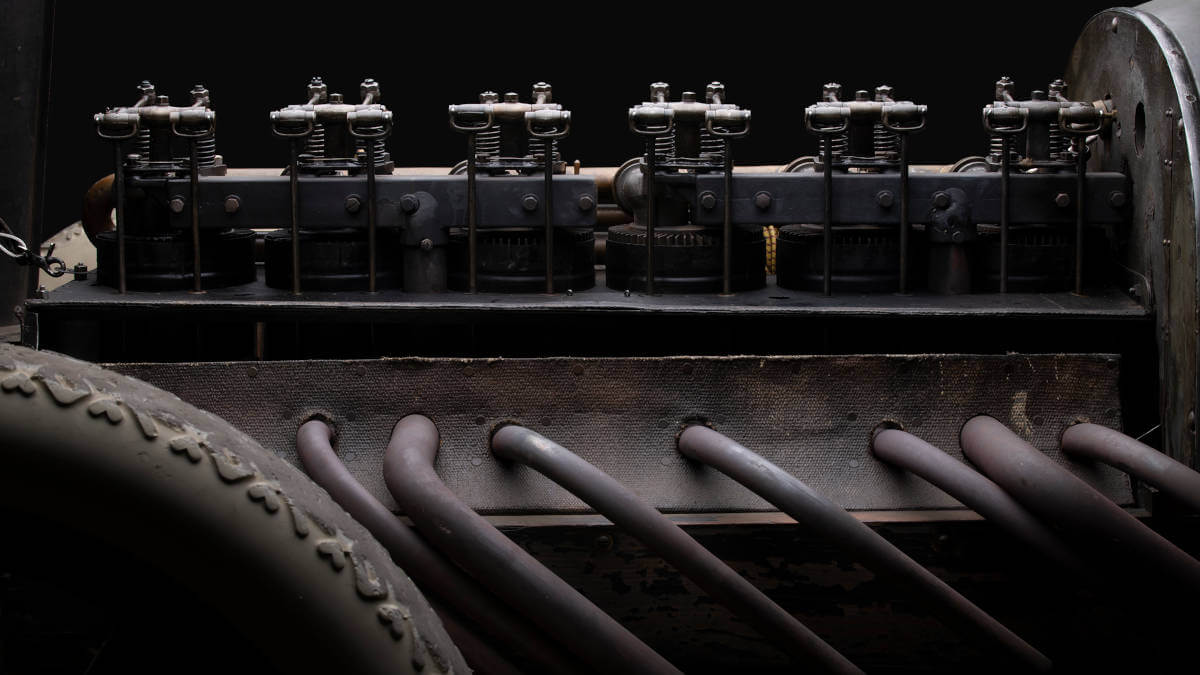

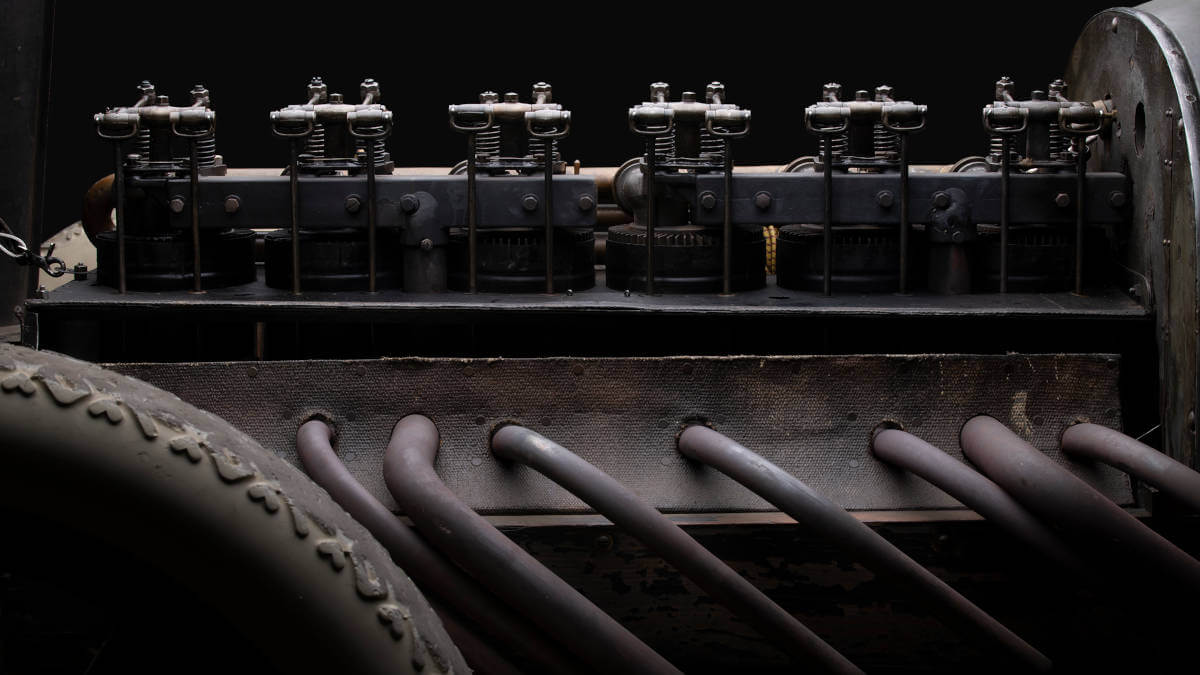

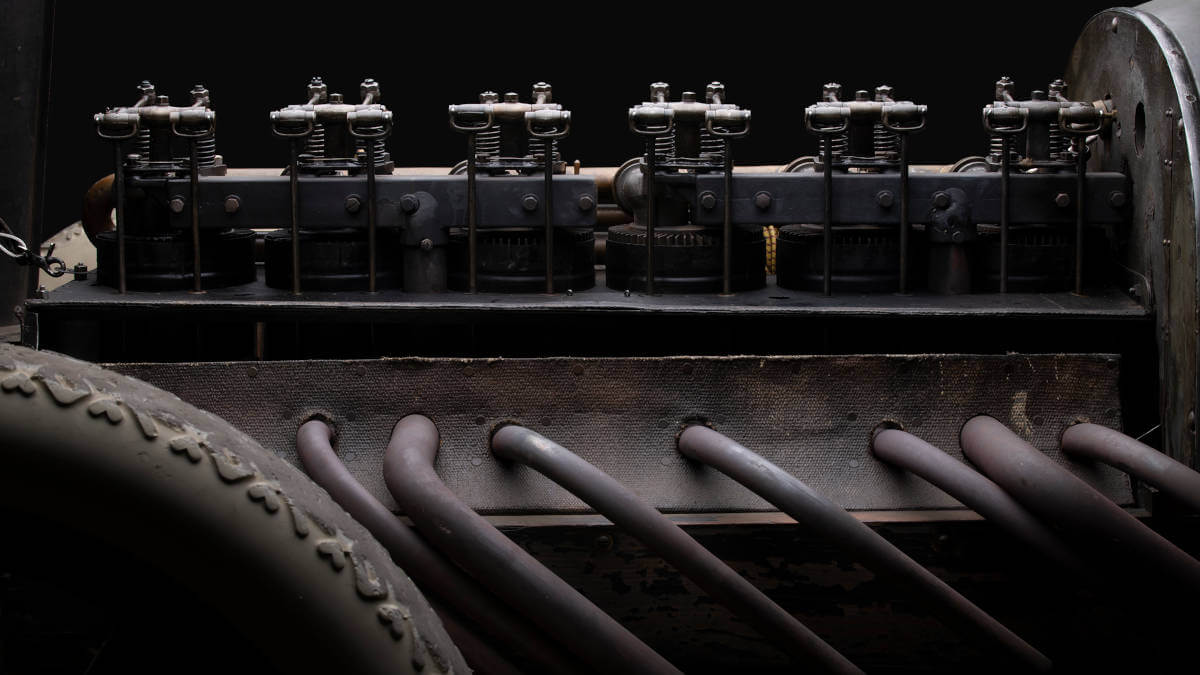

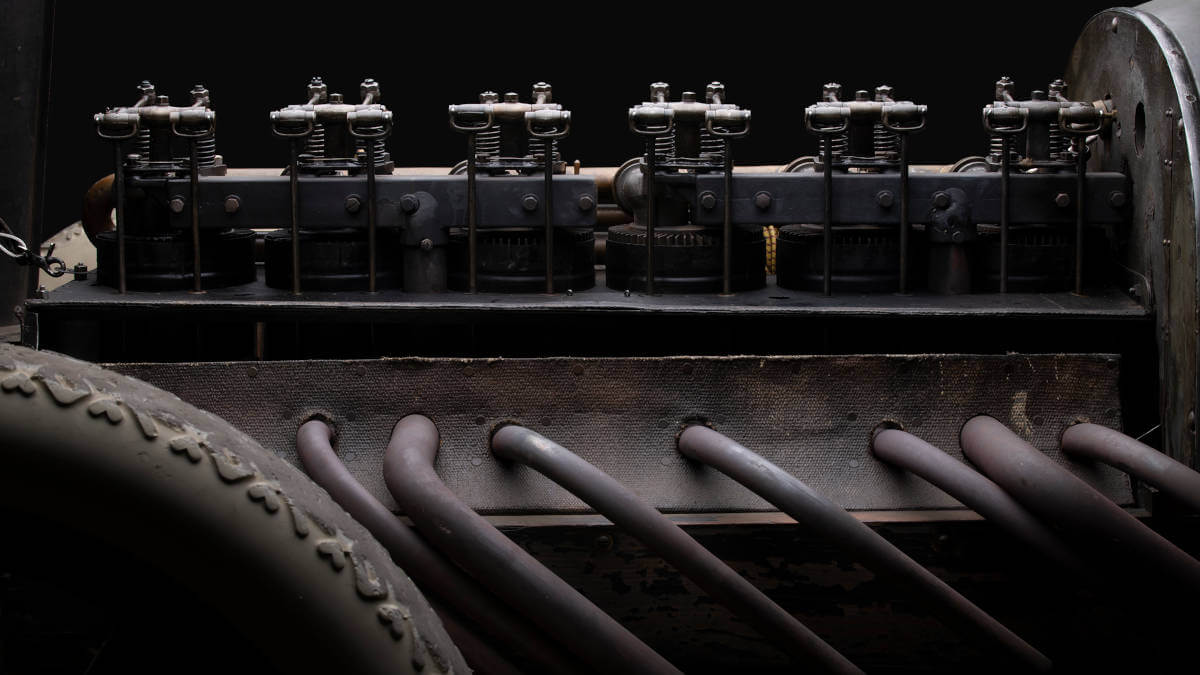

Hemmings writes: “The car was right in 1911, and it’s still right today.” The Times called it “one of the snappiest engines ever turned out by the Syracuse factory,” accurate in more than one sense, as it’s the most pummeling, staccato engine noises we’ve ever heard. The exhaust pulses are distinct and, thanks to the Franklin exhaust valve at the bottom of the cylinder, slightly irregular. Just at idle, it’s akin to having someone toss lit firecrackers at your head–snap, snap, snap, snap, snap. You can feel the air compressing as exhaust explodes from the six little and two big, wicked open pipes, pummeling you back a step.

The owner fired it up and took it for a spin before we began the shoot. There’s no way anyone would ever think “car,” because “low flying warplane” is what comes to mind. It’s a wall of pure power.

This story and car has changed my appreciation for pre-war cars, and this automobile and the people around it birth many innovations and automotive sports that we enjoy today.

1911 Franklin Model D – Details – by Matthias Kierse

For readers born after 1970, pre-war cars are probably no longer part of their everyday picture. They aren’t seen in traffic, in the garage at home, or even as posters in the teenagers’ room – unless your family has a personal history with them. If grandpa and dad have fun with these wild cars and maybe even a small collection is available, one finds a faster access to this topic than if one knows automobiles only with catalytic converter, power steering and ABS. But all these conveniences, which are taken for granted today, had to be invented first.

On the European side of the Atlantic, the Franklin race car is an almost unknown phenomenon. Even the 500-mile race across the desert of Arizona will probably have been unheard of for many of our readers. And yet this car and its history represent important building blocks on the road to our world today. If it weren’t for such pioneering efforts, who knows what today’s cars would look like – if they existed at all. Hamlin’s car often bore the brush-on nickname Greyhound, referring to its agile driving performance.

Our pictures show a Model D from 1910. It demonstrably took second place in the Desert Race that year and was subsequently used for only a few other racing events. Whether this included the Desert Race in 1911 cannot be said for sure. In subsequent years until 1970, the Franklin sat unused in the showroom of a car dealer in Oklahoma. The following owner put the car in storage for about two more decades. It has since been owned by a collector. To date, no restoration has ever taken place, giving this race car an authentic demonstration of what it must have been like to drive through the desert in the early 1900s. Especially with a theoretically possible topspeed of 85 mph, without seat belts, roof or large windshield. Do you now guess why the racers of that time are often described as ‘heroes’?

Nowadays, no other car is known to exist that participated in the Desert Race back then. Since they were racing cars, they were often driven until they broke down and then scrapped. Sentimental or even monetary value was attributed to such cars only decades later. As is well known, this development also occured much later with cars such as the Ferrari 250 GTO. The value of the Franklin Model D today is difficult to quantify, as there is no comparable second example.

Incidentally, there was never an official name for the Desert Race. In the press at the time, the name ‘Desert Race’ was accompanied by ‘Cactus Derby’ or ‘Sand Party’. Among the participating drivers, however, it was the ‘Los Angeles to Phoenix Desert Race’ or just the ‘Desert Race’. It was held once a year from 1908 to 1914. The route to be taken changed each time, resulting in driving times of between 16 and 35 hours. Between sandy dunes and rocky passages, the route also went through steep canyons and over passages with sharp stones.

Tire failures were as much a part of the daily routine as mechanical defects due to heat and overuse. However, it could get so cold at night that even snow wasn’t uncommon. Sandstorms sometimes blew during the day. In some years, rivers burst their banks due to heavy rainfall. And on some passages of the route the drivers had to negotiate with Indian tribes to cross rivers. Not to be compared with today, when you can drive from Los Angeles to Phoenix in about five and a half hours on the well-developed Interstate 10.

History of the Desert Race

Only in the first race held on November 9, 1908, all four competitors did actually finish. In addition to the air-cooled Franklin, there were two water-cooled cars and a steam-powered Steamer, for which water tanks were hidden along the route for refilling. Since Ralph Hamlin lost his way in the darkness towards the end of the day, he finished in last place.

In 1909, ten cars took part, including three drivers from the first edition. However, only four participants reached the finish line. Hamlin destroyed the rear axle housing when driving too fast over a railroad crossing. In 1910, the Franklin finally took second place among 14 participants. Only three cars failed to finish. To allow more live spectators to see this event, the ‘Howdy Train’ was driving along parallel to the track, stopping at certain points. In addition, the ‘Howdy Band’ greeted all participants at the finish line. Already at the start in Los Angeles, about 100,000 people were on site – at 11 pm at night!

The following year, 1911, the organizers shifted the route initially southward via San Diego and eventually even partially across the border into Mexico and back again. Of 16 cars that went on that 542-mile tour, 10 finished. Hamlin again reached second place after losing a lot of time along the way due to a damaged suspension. For 1912, the field dropped to 12 participants, of which only six rolled to the finish line. Hamlin with his Franklin won. He then made good on a promise to his wife: if he ever won the Desert Race, he would end his racing career.

On November 8, 1913, 25 cars set out on a 564-mile race. Only eight were to reach Phoenix. The first place finisher outclassed the other drivers by over two hours. Finally, in November 1914, the final edition of the Desert Race covered 696 miles and had 27 entrants. Once again, only eight finished. Barney Oldfield used his Stutz race car, with which he had finished fifth in the Indy 500 that same year. Although it was considered unfit, he ended up winning the race with it. On the way, the drivers first had to deal with rain and muddy roads. A snowstorm followed at El Cajon Pass and a hailstorm just before the Mojave Desert. The Howdy Train missed a participating Ford by just a few meters at a railroad crossing.

Authors: Matthias Kierse, Bill Pack

Images: © by Bill Pack