Bugatti and the Targa Florio

148 kilometers (92 miles) per lap and five laps in a row, driven at top speed and best time – a distance unimaginable today. And all this on only rudimentary sealed-off country roads that weren’t completely asphalted in the early years. Of course we are talking about the legendary Targa Florio road race in Sicily, which was first held in 1906. In 1919, the organizers shortened the lap length to 108 kilometers (67.1 miles), and in 1932 it was finally reduced to 72 kilometers (44.7 miles), while still retaining the Buonfornello straight along the beach, which, with a length of more than six kilometers is even longer than the famous Hunaudieres from Le Mans in the pre-chicane era. Training sessions before the actual race took place in flowing traffic. Yes, racing in the early days of the automobile was dangerous and much more exciting than today’s Formula E buzz. However, this anachronism actually lasted until 1977, while this event still achieved world championship status for the Sports Car Championship. Afterwards, from 1978, some parts of the track were used as special stages for the Rally Targa Florio, which is still held annually.

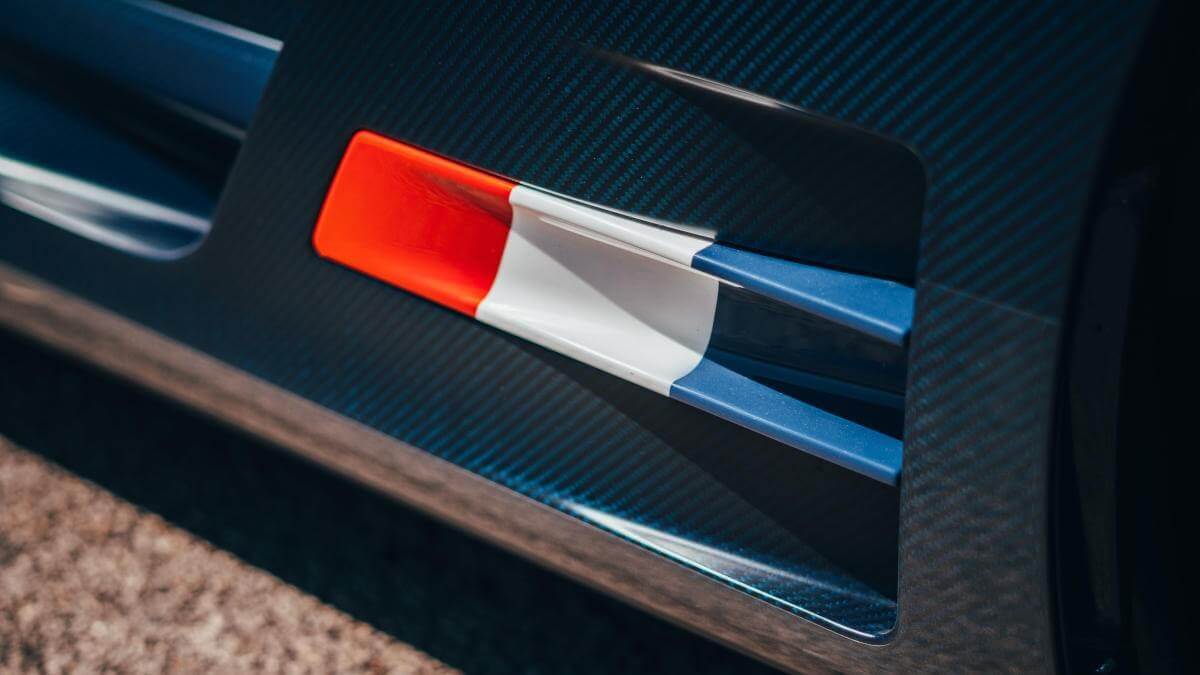

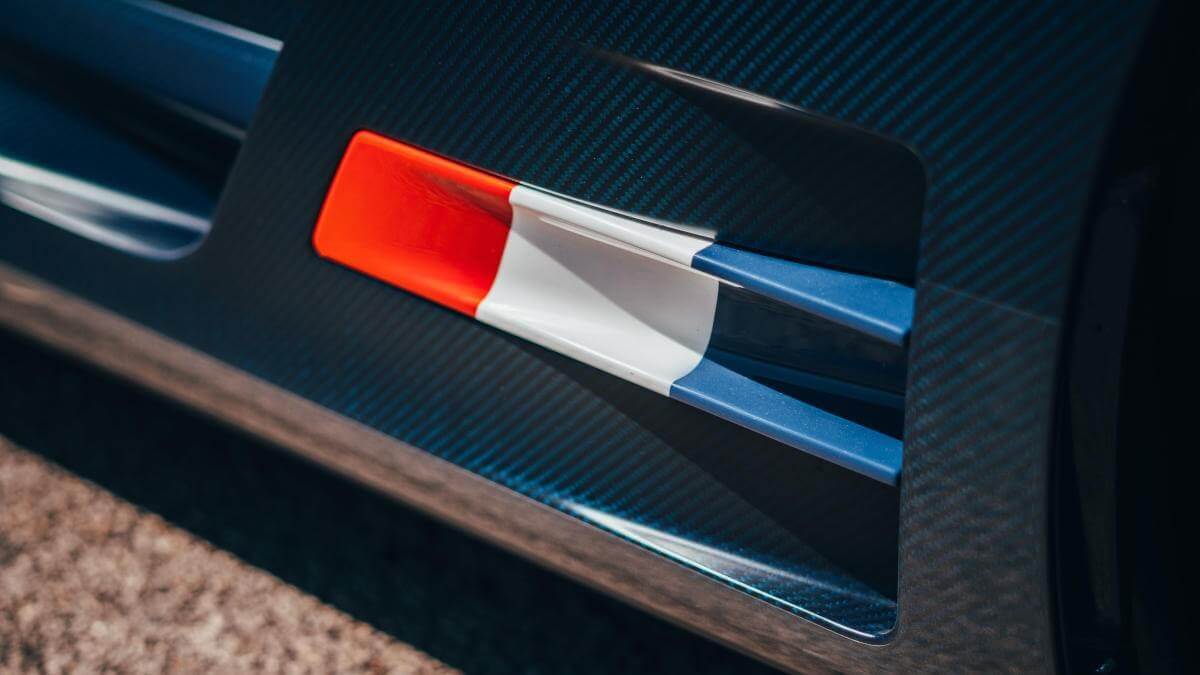

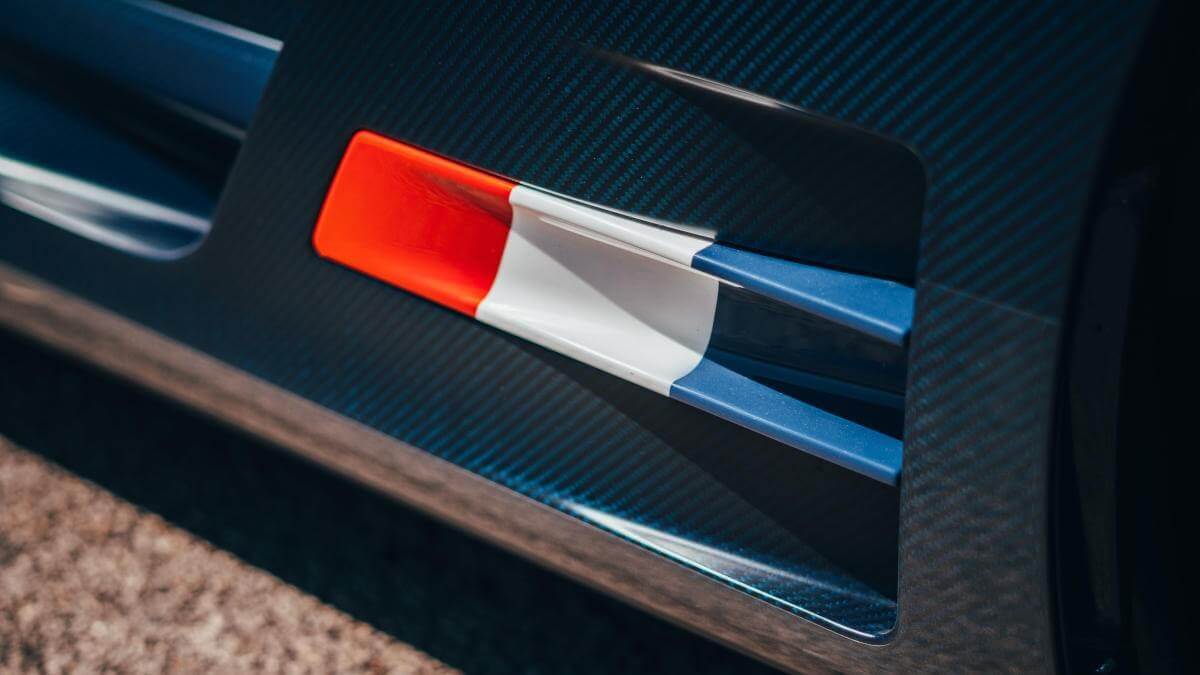

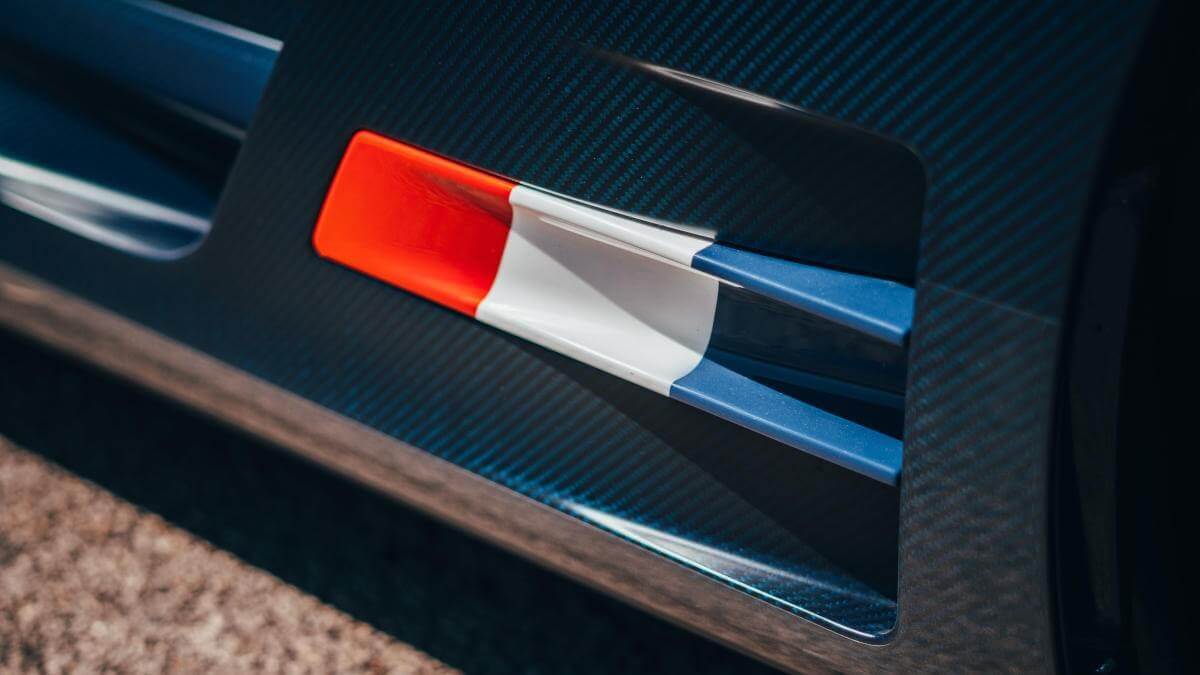

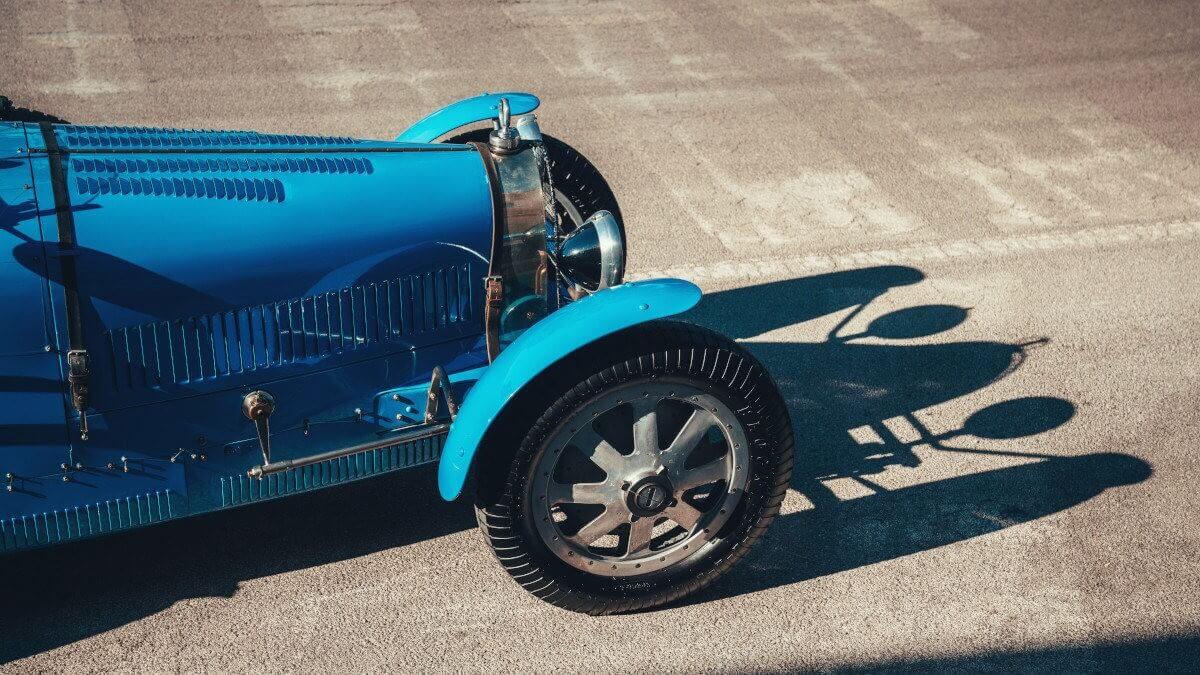

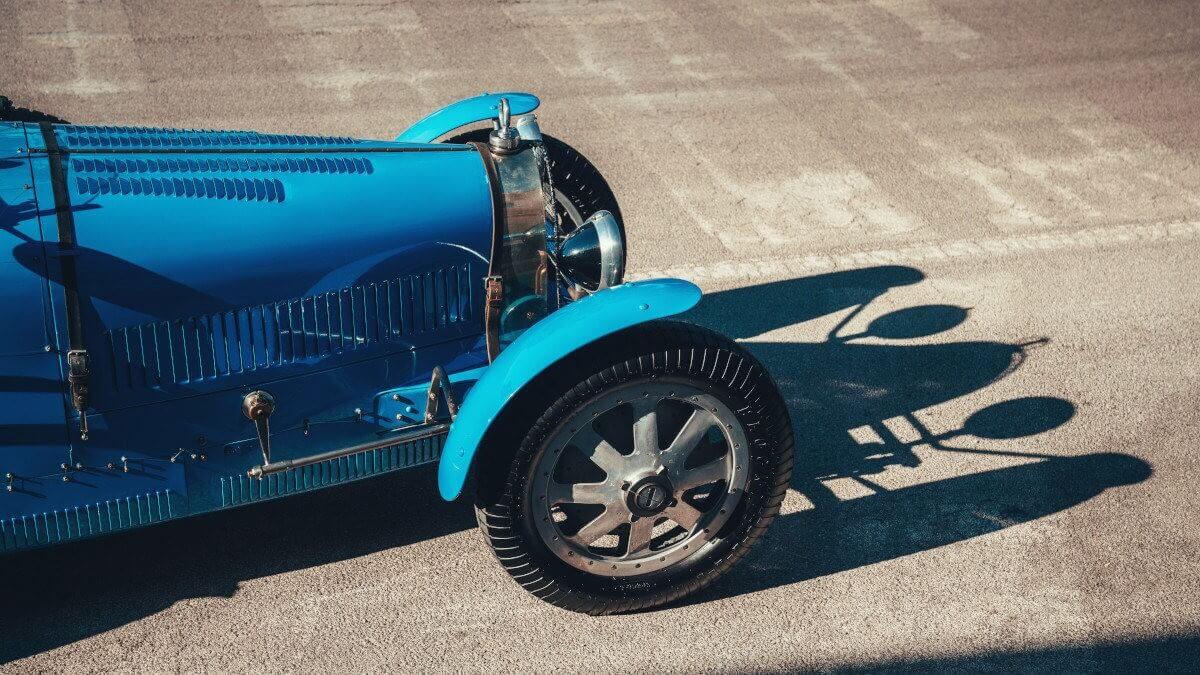

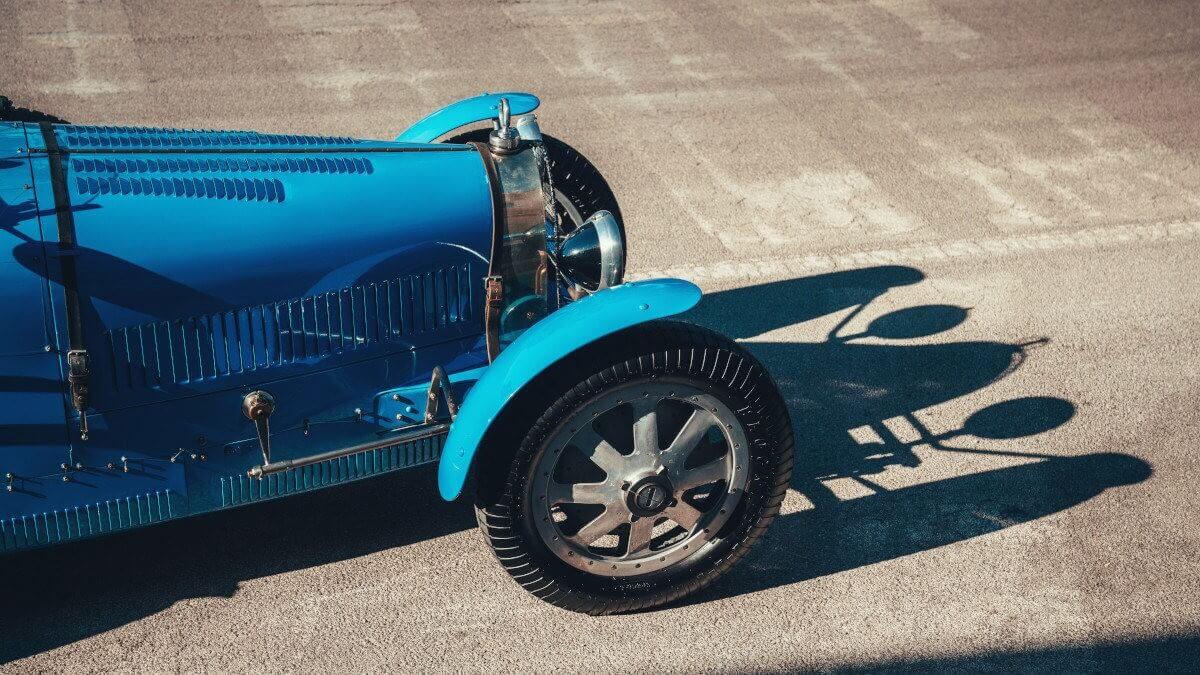

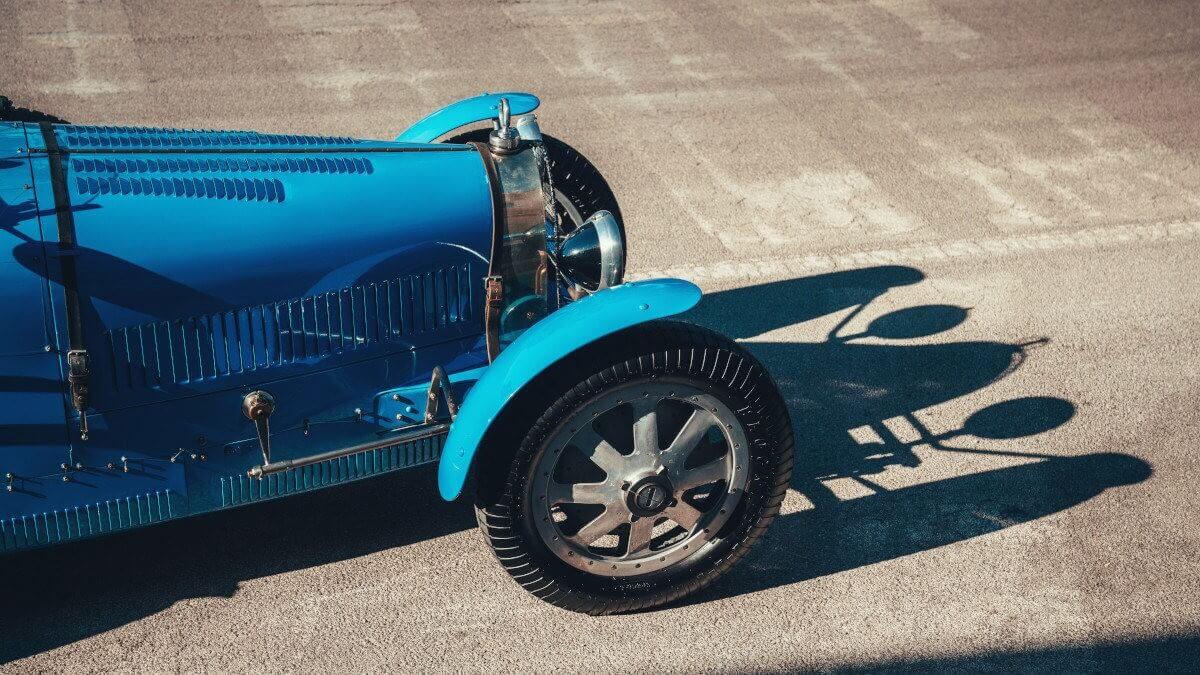

One car brand is particularly associated with the early days of the Targa Florio: Bugatti. After a few private drivers had already scored minor successes here, the factory team finally arrived in the mid-1920s. In 1925 and 1926 the Italian racing driver Bartolomeo Costantini won the race, driving a Bugatti Type 35 (1925) and a Type 35T (1926). A year later, his compatriot Emilio Materassi followed him to the top of the winners’ podium with a Type 35C, and finally, in 1928 and 1929, Albert Divo achieved two more overall victories with a Type 35B and a Type 35C. Today’s Bugatti company is currently erecting a mobile monument to the French works driver in the supercar Divo, limited to 40 units. Such a car and a Type 35 were now sent for photo laps on parts of the former track for the sports car world championship.

The technical basis of the Bugatti Divo comes from the Chiron. This means that 1,500 hp is available, which is generated in an eight-liter W16 engine by four turbochargers. These are transferred via a seven-speed dual-clutch transmission to the permanent four-wheel drive and then to the four wide wheels. After just 2.4 seconds, the Divo reaches 100 kph (62 mph), with a maximum speed of 380 kph (236 mph) possible. This is achieved by sophisticated aerodynamics, with a wide NACA duct in the roof directing fresh air to the engine, while a 1.83 meter wide rear wing together with a wide front spoiler provide plenty of downforce. Flat C-shaped LED headlights and complex, three-dimensional LED taillights provide extremely unusual illuminated graphics at night.

In comparison, the Bugatti Type 35 seems incredibly underpowered from today’s perspective. The fact that in the 1920s a two-liter inline eight-cylinder engine with initially around 95 hp was sufficient for major racing victories seems incredible. However, this engine performance, which was later increased to 140 hp by means of supercharging and increasing the displacement by 0.3 liters, only met with a low total weight and thus made the Type 35 more than 180 kph (111.8 mph) – in later versions even 215 kph (133.6 mph) – fast. For the photo drives, chief test driver Andy Wallace took a seat behind the wheel of the classic car. Although he himself won the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1988 with a Group C car from Jaguar, he admires the achievements of the Bugatti drivers some 90 years ago: “What the racing drivers like Albert Divo achieved back then is incredible. Even though the Type 35 is easy to drive for its age, permanent muscle work is required. The many curves are tight, the track is confusing and the asphalt is in a very bad condition. Overtaking isn’t possible”. He then circumnavigated the course in the new Divo and summarized his impressions as follows: “I am deeply impressed how the Divo, which is designed for much higher speeds due to its dynamics, copes with these sometimes very bad roads and short sections until the next corner. Steering, springs, dampers, control systems, transmission and brakes respond very directly and precisely to every driving command. Even after large bumps, the springs absorb energy very quickly so that the Divo never loses contact with the ground – an outstanding achievement by the developers”.

Images: Bugatti