60 Years of the Alpine A110

With the Alpine A110, Jean Rédélé achieved a great success 60 years ago. And yet the vehicle itself was so small and flat that in France it was nicknamed “le Turbot”, the flat fish. Nevertheless, the A110 managed to drive its way into the hearts of sports car and rally fans. The lightweight car remained almost unchanged in the range until 1977. Technically, the flounder developed up to 240 hp over the years. In the 1950s, Renault also produced some interesting vehicles. Sportiness, however, wasn’t necessarily one of the core arguments with which they could be advertised. This didn’t sit well with a Renault dealer in Dieppe on the Channel coast of France at all. After all, a lot could already be made out of vehicles like the 4CV by simple tuning. He proved this, among other things, by winning the Coupe des Alpes in 1954.

From dealer to car manufacturer

In order to at least earn money in his customer base with his sporting successes, he began to build his first own sports model on this basis the following year. He gave it the name “Alpine” in memory of his victory. It was the Alpine A106 with plastic bodywork and a tuned 4CV engine. Who was this dealer? None other than Jean Rédélé, whose name still has a good ring to it among rally fans today. However, neither his own sporting successes nor his dealership are to blame. Even the A106 was only a first taste of his skills, but not a great sales success. Likewise, the Alpine A108, introduced three years later, wasn’t one, although it was available as a coupé or convertible. In retrospect it is a trailblazer with numerous sporting successes. Compared to the car with a special anniversary, which is actually the subject of this report, it was a small light in the history books of the French automobile industry.

A110 made its debut in Paris

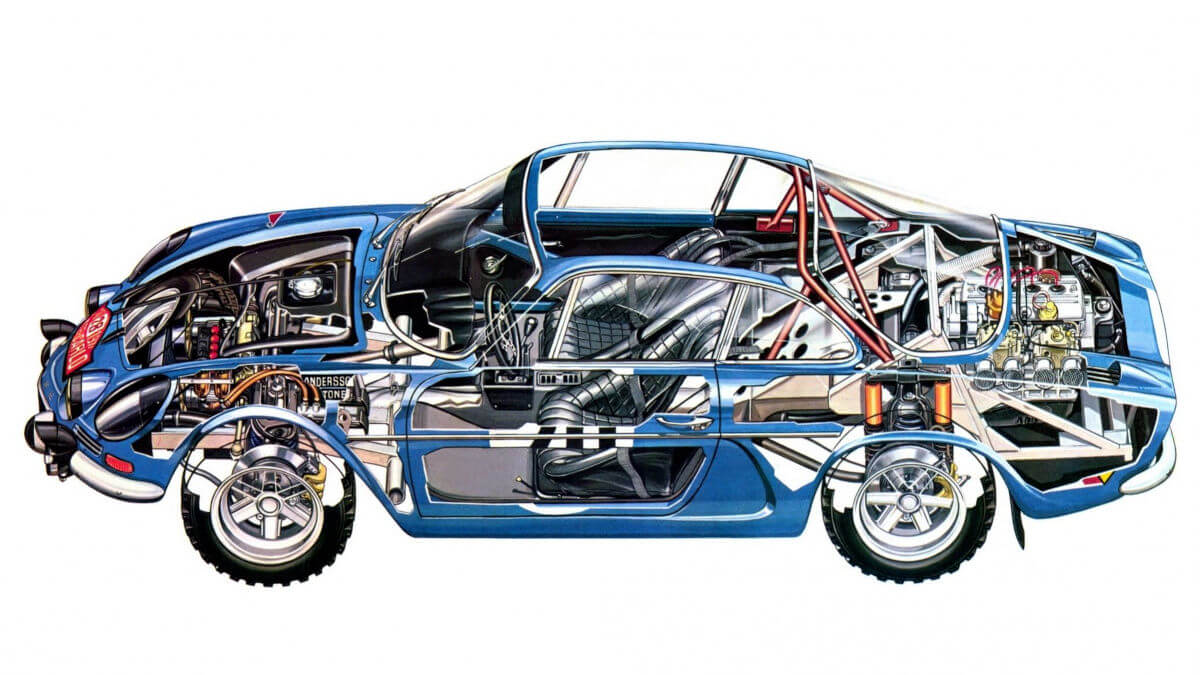

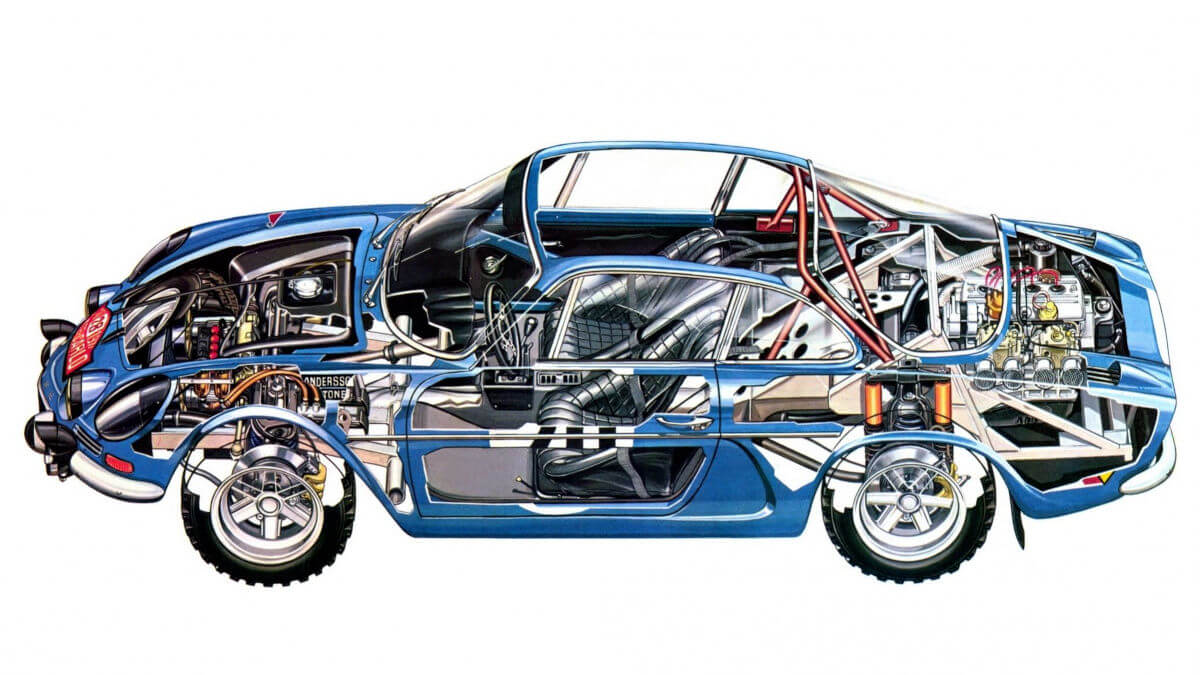

In 1962, at the Paris Motor Show, the time had finally come: the experts paid attention and the visitors to the fair were wide-eyed when they saw the new A110 Berlinette with the additional name “Tour de France”. None of the onlookers at the time could have guessed that this vehicle would remain in the range for a full 15 years and turn the rally world upside down in the process. The body shape, which was already quite convincing in the A108, was lovingly developed further without losing its dainty style. The overall vehicle was only 1.13 meters high and 3.85 meters long. Thanks to the continued use of plastic construction for the body, a central tube frame chassis and the rear engine of the Renault 8, the total weight was initially a low 565 kilograms. Over the years, it increased due to several model updates and different engines, but from today’s point of view it was still surprisingly far below the one-ton mark at 730 kilograms in the last version.

Initially only 52 hp

The engine, with its initial 956 cc, was increased in power by Rédélé and his team from the standard 44 to 52 hp (38 kW). Combined with the low weight and streamlined body shape, this was sufficient for a topspeed of 170 kph (105 mph). Power was transmitted via either a four- or five-speed manual gearbox. In contrast to the A108, the radiator in the Alpine A110 sat behind the engine rather than in front of it, which meant that the side cooling air intakes were no longer needed. Smaller inlets to the left and right of the bonnet replaced them. In later versions, and especially for rally use, these were given small “ears” in order to use the airstream even more effectively for cooling. Like its predecessor, the A110 was quickly discovered by motorsport enthusiasts as an ideal vehicle. Just as quickly, word got around about its excellent driving characteristics, which led to many orders from France and abroad.

Many engine variants followed

At the same time, Jean Rédélé continued to develop the car and installed more and more new variants of the engines he had tuned. Depending on the customer’s wishes, new connecting rods, larger intake valves, sharper camshafts, new pistons, larger carburettors and specially manufactured manifolds were installed. All to breathe more steam into the Renault engines. Customers always had the choice of receiving their ordered vehicles in competition or road-going version. Just four years after market launch, the 80 hp mark was dropped, making 200 kph (124 mph) possible on flat roads. In addition, variants of the A110 were available with 1.1-liter engines from the Renault 8 Major and later from the Renault 8 Gordini, steadily tightening the performance screw. “Engine wizard” Amédée Gordini worked with Marc Mignotet for Rédélé to get more power under the A110’s lightweight plastic skin.

Radiator moved to the front

In 1965, Alpine launched the A110 1300/S, then the top model, in parallel with the 1.0 and 1.1 liter versions. The Gordini engine was given a power output of 92.6 hp per liter by increasing the displacement to 1.3 liters and using the full range of tuning available at the time. In other words, a total output of 88 kW/120 hp. This allowed “le Turbot” to run at speeds of up to 228 kph (141 mph), which back then meant an ascent to the sports car Olympus. To ensure better cooling, the radiator of the A110 1300 moved from the rear to the front. This also helped the weight distribution and thus the driving dynamics. Jean Rédélé was also able to secure a distribution agreement with Renault. This meant that his sports cars weren’t only serviced at Renault dealers, but also offered there in the showrooms. With the introduction of the Renault 16, another four-cylinder power unit once again came to the attention of the Dieppe squad.

With 1.6 liters to 138 hp

It’s hardly surprising that the 1.5-liter aluminium engine was also put to work in Rédélé’s flattop just one year after its debut in the well-behaved family saloon. With more power, of course. As the new A110 base engine, it produced 70 to 90 hp (51 to 66 kW), depending on the version. This helped the flounder to reach topspeeds of between 180 and 190 kph (112 to 118 mph). At the same time, the bodywork was given its first facelift in the form of two fixed auxiliary headlights at the front. But the Alpine A110 only became a real bullet with the adoption of the Renault 16 TS engine with a displacement of 1.6 liters. The team of engineers in Dieppe immediately set to work and presented the A110 1600 S in 1969, a 102 kW/138 hp sports car that was to cause a sensation at international rallies. Up to then, they had been content with class victories and appearances in French competitions.

International rallying from 1968

However, as the sporting activities of Renault and Alpine were merged in 1968, rallies all over the world were at the top of Dieppe’s agenda. And not without reason, as Gérard Larousse almost won the Rally Monte Carlo on the very first outing under the joint flag. Only the snow shovelled into a bend by spectators to increase the tension was his and his A110’s undoing. Both, the 1300/S and 1600 S quickly took their places in the hearts of the specatators. With their rears drifting far out and high-revving naturally aspirated engines, they were a feast for the eyes and ears. But Rédélé and his team were already working on other weapons and to the displacement subsequently increased to 1.8 and then to 1.86 liters. This allowed the power to climb up to 132 kW/180 hp. The reward was a succession of victories and titles.

Wins by subscription

The Lyon-Charbonnières Rally became the Alpine A110’s showpiece. It won there without interruption from 1968 to 1972. But the Coupe des Alpes and the Corsica Rally as well as the San Remo Rally and the Acropolis Rally were also among the success stories of the French flat car. In addition, the A110 won the International Makes Championship in 1971 and the World Rally Championship in 1973, which was held for the first time that year. Meanwhile, a revolution was already at work on the engine test bench in Dieppe. With the help of young engineer Bernard Dudot, Mignotet fitted the engine of the A110 1600 S with a turbocharger, which resulted in a power output of 177 kW/240 hp. For the first competition use, however, this was scaled down to 200 hp (147 kW) to increase durability. This power explosion also required true acrobats behind the wheel. After all, we are talking about the early days of turbocharging in the automotive industry. The prevailing turbo hole was followed by a huge kick in the butt.

Almost 7,500 units until 1977

However, Jean-Luc Thérier was an extremely talented racing driver, who won his first race in the A110 Turbo. At the same time, this was the first success with a turbo-powered car in European motorsport. Dudot went on to develop the highly successful Renault turbo engines for Formula 1 and the Le Mans 24 Hours, as well as the power unit of the Renault 5 Turbo. In 1971, 1,029 examples of the A110 left the Alpine factory in Dieppe. This was the model’s most successful year of production, despite the fact that in March of the same year the successor model, the A310, was already sent onto the production lines. The A310 was produced in parallel until 1977, when the introduction of the V6 engine led to an increase in the number of units produced. Until then, a total of 7,489 Alpine A110s were built in Dieppe. Incidentally, the last car wore a rather untypical green instead of the typical blue still familiar today – the French racing color.

Alpine becomes an electric brand

Next to those cars, licensed versions of the A110 were produced at FASA in Spain, Willys Overland in Brazil and DINA in Mexico. Even beyond the then omnipresent Iron Curtain, between 100 and 150 examples were built at Bulgaralpine in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, on request even as a convertible. To this day, the surviving Alpine A110s are cherished by enthusiasts. The sports car from Dieppe can also still be seen in action at some rallies. In the meantime, a modern reinterpretation has been available for five years now. In the coming years, however, the revived Alpine brand is to change in the direction of electric mobility. Would Jean Rédélé have liked that? One may harbour certain doubts.

Images: Alpine